Pop culture has led to a recent resurgence of passion for using the Taigi language. In 2016, DJ Didilong (李英宏) released renowned song “Taipei Didilong” (台北直直撞); in 2017, EggplantEgg’s (茄子蛋樂團) “Back Here Again” (浪子回頭) became a hit; and the drama series A Boy Named Flora A (花甲男孩轉大人) starring Crowd Lu (盧廣仲) gained popularity across Taiwan. In 2019, the Taiwanese public TV channel, PTS Taigi (公視台語台), was created. Workers (做工的人), The Sound of Happiness (炮仔聲), I, Myself (若是一個人), U Motherbaker (我的婆婆怎麼那麼可愛), and many other Taigi dramas flourished. Furthermore, a Taigi version of The Little Prince topped the newest releases ranking at Books.com.tw (博客來) in 2019.

Does the rise in popularity of Taigi-language media signal Taigi’s rise to prominence? Are Taiwanese youth using the language more in their daily lives? What suggestions have scholars and experts offered when it comes to advocating for Taigi and Taiwanese culture?

Enchanted by the raspy voice of EggplantEgg’s lead singer A-pin (阿斌), the young audience sang and shouted along in Taigi:

“with loved ones we walk, back here again . . . ” (“Tsah bóo-kiánn tàu-tīn, lōng-tsú huê-thâu . . . ”)

EggplantEgg’s “Back Here Again” broke 100 million views on YouTube and it isn’t the only Taigi creative work gaining popularity. A translation of The Little Prince became the first Taigi book to top the newest literature releases at Books.com.tw. A-Hua Sai (A-Hôa Sai), whose Youtube channel (「足英台三聲道磅米芳」) went viral on Facebook, speaks only in Taigi, English, and Taiwanese Hakka – not Mandarin. DJ Didilong (李英宏) collaborated with rapper Soft Lipa (蛋堡), releasing an entirely Taigi-style song on DJ Didilong’s new album Sweet (水哥).

The first resurgence of Taigi’s popularity was ushered in after martial law was lifted in 1987, most notably through music. The New Taiwanese Song Movement (新台語歌運動) left a profound impact on Taiwan’s cultural sphere, brought about by Blacklist Studio (黑名單工作室), Lim Giong (林強), Chen Ming-chang (陳明章), Wu Bai (伍佰), and many others. In recent years, a second wave of Taigi revitalization has emerged.

Previously, the Taigi language was a dry subject taught in local culture curriculum– now it is experiencing a glow-up, finding its voice on social media platforms and in youth communities.

“I’d really love it if Taigi elements are incorporated into product design,” said Tsao Yung-han (曹詠涵), an interviewee born in the 90s who moved to northern Taiwan from Chiayi for work. Tsao believed it would especially be appealing if some advertising slogans were spoken in Taigi.

Since Tsao was a child, she sometimes spoke with her family in Taigi and often watched Taigi soap operas (鄉土劇) with her mother. She believed Taigi is simply a form of communication and felt that elders are more amicable when communicating with them in Taigi. She said frustration can arise when conversations get stuck using infrequently spoken Taigi words, sharing that “[I feel a sense of] guilt that I cannot speak my own native language well.”

Yang Tzu-hsien (楊子賢), also born in the 90s, after completing his studies in Taipei, returned to his hometown, Changhua, to serve as the Chairman for the Sulfur Creek Cultural Sustainability Association (磺溪文化永續協會).

Yang speaks mostly Taigi in daily life and has observed that speaking in Taigi is treated as an ‘identity marker’ to some degree nowadays. For example, AmazingShow’s (美秀集團) song “Chicken” (一隻雞) is about how the usage of Taigi was banned under authoritarian-era cultural policy. The chicken’s inability to fly symbolizes the trying condition Taiwanese people faced when not allowed to speak their native languages. Many young indie artists try to write song lyrics using Taigi, increasing the likelihood of people's exposure to Taigi.

Yang emphasized that “it doesn’t matter what your native language is, as long as you identify yourself with Taiwan, you are Taiwanese.” While this is true, he also acknowledged that he feels a deeper sense of connection when speaking in Taigi with friends from south-central Taiwan who moved to northern Taiwan for study or work. Yang explained that this is because he feels a faint sense of intimacy when speaking in Taigi with these friends. His experience indicates that language and identity are intricately interrelated.

For the younger generations, this is perhaps the first time they have seen a wave of Taigi revival spurred by independent music groups. Earlier in the 1990s, Taigi became all the rage for a short while because of the New Taiwanese Song Movement. But what are the differences between these two waves of revival?

Wang Horng-Luen (汪宏倫) has been conducting long-term research on nationalism at Academia Sinica’s Institute of Sociology. He observed that the emergence of a Taigi-language movement in the 1990s was a direct challenge to the KMT's prolonged suppression of and discrimination against Taigi and Taigi-speaking communities. It also embodied the resistance of a nascent nativist movement against the KMT’s China-centered discourse and authoritarian rule. For example, when he attended pro-independence gatherings while studying abroad, he was encouraged to speak and communicate in Taigi.

Wang believed that the recent upsurgence in Taigi popularity is related to the rise in Taiwanese awareness and identity after the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) came to power. Throughout this time, young people have gradually become aware of the possibility of losing their language heritage. Comparing the two waves of Taigi revival, Wang stated, “at the time [in the 1990s], the target of oppositional politics was the KMT— now it is China.”

However, he emphasized that this is one of the only reasons that more young people are speaking Taigi. It is dangerous to use language to differentiate between the self and the other, causing unnecessary hostility between groups. He used the example of civic nationalism instead of language, ancestry, or ethnicity as the model for the foundation of Taiwanese identity. So long as people share a civic identity, they can identify with one another. Only in this way can Taiwanese society become more tolerant and inclusive to different forms of national identification.

The first Taigi wave from the 1990s could not sustain its momentum — to this day the cause has yet to be determined. Associate Professor Yap Ko-Hua (葉高華) from the Department of Sociology at Sun Yat-sen University believed that revitalization comes in waves. Sometimes issues are stirred up for debate, later drifting into silence. Despite this, the ability to speak one’s mother tongue continues to deteriorate with each following generation. Lu Dong-shi (呂東熹) – director of PTS Taigi, the public Taiwanese language TV channel – speculated that the wave of Taigi popularization in the 1990s could not be sustained most likely due to the opening of cross-Strait exchange and the increasing interaction between Taiwan and China. An increasing number of performing artists considered working across the Strait, causing them to speak Taigi less.

PTS Taigi launched the program A Phrase A Day (逐工一句) to teach Taigi vocabulary and phrases to netizens, using the visual style and comedy presentation format preferred by younger generations.

Tu You-jen (涂又仁), the host for A Phrase A Day, observed that music and drama series have changed the outlook young Taiwanese people have towards Taigi, playing a pivotal role in the popularization of Taigi in recent years.

Now thirty year-old, Tu expressed that “the emergence of these singers like DJ Didilong allows young Taiwanese to gradually perceive Taigi as being cool and unique.” The album and hit single “Taipei Didilong”, released by DJ Didilong in 2016, has not only become a hit whose lyrics many people can recite, but was also nominated by the Golden Melody Awards for Best Album in Taiwanese and Best Male Vocalist-Taiwanese.

Then in 2017, EggplantEgg released their album Cartoon Character (卡通人物) – songs like “Back Here Again” slowly rose in popularity. In addition, that year the drama series A Boy Named Flora A《花甲男孩轉大人》 became widely popular all over Taiwan. Resonating with young people, these works have created a turning point for the popularization of Taigi.

Now that A Phrase A Day has become a popular program on social media, Tu and the director of the program Chou Chia-Ying (周佳穎) reflected that the cause for its rise in popularity can be attributed to its comedic style, lively plot structure, and its adoption of the visual style preferred by Taiwanese youth.

“The opening and closing music is played by Teacher Tēng-pang (周定邦; Suyaka Chiu) using, a traditional 4-stringed instrument, the yue-qin”. The program’s blend of new and traditional elements creates a sense of freshness, successfully attracting a broad audience.

Tu explained that in the past, many TV programs and creative works gave viewers a negative stereotypical impression of Taigi. For example, the majority of Taigi-speaking roles in such films or dramas were depicted as “hoodlums” or as people who haven’t received a high level of education, making it appear that Taigi is only used in a vulgar manner. However, the previously mentioned music productions, dramas, and characters are creating new trends for young people to follow, while subtly shifting people’s stereotypical perception of Taigi.

“Come, let’s see which corner seat is best”, said Gustave Cheng (鄭順聰), a loud-spoken Taiwanese writer. Cheng had no wish to disturb other customers. Upon entering the coffee shop, he tried to find the best spot for the interview. He spoke Taigi well and gently.

People often perceive Taigi through the stereotypical images of crudeness or unruliness, as if Taigi is only used and spoken at places like the morning markets, temples, construction sites, or Taigi soap operas. In the past, film and TV shows often linked the image of Taigi with that of the gangsters or rural areas. Cheng, however, has his own opinions.

“I had an interview a few months ago and made special arrangements to meet the [Taigi-speaking] interviewee in Xinyi district.” To Cheng, every language is of equal status. You can use Taigi when shopping, having a meal, or clubbing in the Eastern District of Taipei. The purpose of expanding Taigi usage is not to surpass Mandarin, but to make Taigi a part of daily life.

To illustrate his point, Cheng brought up Taigi works such as Workers (做工的人), The Sound of Happiness (炮仔聲), and romantic idol dramas like I, Myself (若是一個人). The development of Taigi drama is multifaceted. He believed that the popularization of Taigi in recent years cannot be solely attributed to a single cause. Practical use, emotional attachment, political recognition, and the beauty of the language are all motivating factors.

Because of this, Taigi dramas come as a sign of victory. At the beginning of June 2020, the release of U Motherbaker (我的婆婆怎麼那麼可愛) on PTS Taigi was regarded as yet another success. Lu Dong-shi (呂東熹) indicated that in addition to the widespread internet popularity, the viewership also exceeded his expectations, closely following behind the high viewership ratings for soap operas on commercial channels like Formosa Television (民間全民電視公司) and Sanlih E-Television (三立電視).

Outside film and TV programs, there are many other regular markets and customers for Taigi-related productions and products. Recently, more such products have emerged, including board games, washi tape, movies, video games like “Halflight” (夕生) and “Pagui” (打鬼), and fonts like “Jin-hsuan” (金萱體).

Gustave Cheng believed that Taigi can become an excellent tool for displaying Taiwan’s unique characteristics to the world. When almost every video platform provides subtitles, what was seen as a language gap in the past will no longer be a problem. Works from Korea, Thailand, and India have succeeded in finding what makes them unique, gaining a foothold in the global film and television industry, despite using their respective languages in production.

The process of producing different styles of Taigi works is not as easy as one can imagine, however.

“When taking Taigi language courses, I felt like I was about to go crazy every day, and debated whether or not I should switch roles,” Ryan Tu (杜政哲) recalled about his preparations for film production. Screenwriter and director for Taiwan’s first Taigi romantic idol drama I, Myself (若是一個人), Tu could recall the feeling of anxiety and stress from that time. Some actors had never spoken Taigi. Throughout the production process, however, they had to get used to speaking Taigi in a short span of time.

To overcome the public’s stereotypical perception over Taigi-speaking drama, the setting and casting played an extremely important role. Tu admitted that when looking for people to cast for the drama, there were actors who refused to take up the role because they did not speak Taigi or because they worried that taking a Taigi-speaking role would have a negative impact on their career. His lead female protagonist was played by Sun Ke-fang (孫可芳), who had a basic understanding of the language. Other actors like Edison Song (宋柏緯) had no experience speaking Taigi .

Because most of the actors had seldom spoken Taigi, they were required to take an intensive Taigi-language course. Everyone took turns taking the course; however, actors playing important roles were given one-on-one Taigi tutors. Even on the set, there were Taigi teachers to coach the actors. With diligence and hard work, the actors reached a certain level of Taigi proficiency. “There are plenty of people in Hollywood who speak poor English. In Taiwan, of course there are people who can’t speak Taigi well.” The director perceived the actors’ inaccurate pronunciation of Taigi as another way of staying true to reality.

Tu hoped that the audience can overlook their perceptions about languages when watching the drama. After all, language is a tool to convey emotion. As long as the emotion feels real, there is no need to be picky about language use.

The development of Taigi should be multifaceted. Yokita Lim (林良儒), a Taigi tutor with over 12-years of experience, shared a similar thought: “We are causing harm to the Taigi language if we focus only on one of its many aspects —be it its beauty or abrasiveness.” He explained that one should appreciate the many faces of Taigi, treating it the same way as Mandarin.

In 2016, he created the Facebook page “Out-of-Control Taigi Class” (失控的台語課) in hope of attracting young language learners and kindling their interest in Taigi. He shared a variety of activities and lessons related to the language – his page has already surpassed 60,000 likes, becoming a model Taigi-language Facebook page.

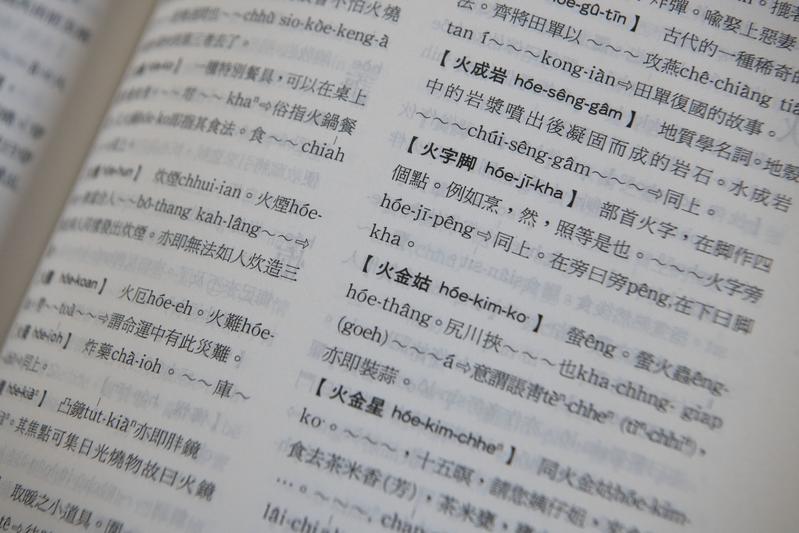

Having dropped out of the School of Medicine of National Yang Ming University (陽明大學醫學系), Lim offers Taigi-language courses at Yang Ming University (陽明大學), Taipei Veterans General Hospital (臺北榮民總醫院) , Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital (台北慈濟醫院), and other institutions. “Only when doctors can understand and speak Taigi can they better comprehend the pain of their patients,” because Taigi is rich with descriptive words. To name a few examples, pregnant women would say tiam-tiam (砧砧) to refer to a prickly feeling they experience when their belly skin is stretched. Other patients might describe an eye condition as sīnn-sīnn (豉豉), a feeling similar to having a few drops of sea water getting into one’s eyes or rubbing salt into one’s wounds. It is very difficult to use Mandarin to capture such sensations. Doctors and nurses might be able to make better judgments if they can understand Taigi.

However, this language barrier does not only exist among medical professionals. A lot of knowledge becomes inaccessible in professions such as suit-making and bone-picking. Taigi can be used to fluently explain valuable techniques in these professions. The meaning becomes lost when using other languages like Mandarin, where only the general idea can be described. The inaccessibility of knowledge might lead to the gradual extinction of many areas of expertise. Yet, with a growing public awareness of the erosion of Taigi, more and more people have been organizing Taigi-spoken activities. Lim observed that before the outbreak of COVID-19, Taigi-related lectures were hosted every week in Taipei, with young people in frequent attendance. A group of mothers also formed a Taiwanese playgroup, setting up the Facebook page “Leading Our Children Down the Taigi Road” (牽囡仔ê手 行台語ê路). They organized regular gatherings to create an all-Taigi learning community.

Taigi has become popular amongst young people, but can its popularity truly permeate into their lives to revive Taigi?

“When I delivered lectures, I used Taigi to say good morning to everyone. More than half of the students responded with blank faces,” said Yap Ko-Hua. When discussing whether more and more young people speak Taigi, Yap wasn’t optimistic. He once conducted a poll at Sun Yat-Sen University where, despite its location in southern Taiwan, only 20% of the students could speak Taigi.

Yap pointed out that if one observes the entire trend of Taigi usage, as in Academia Sinica’s 2013 “Taiwan Social Change Survey” (台灣社會變遷基本調查), one would find that the use of local languages is in decline. The younger the generation, the more Mandarin is spoken, and the less Taiwanese Hokkien (Taigi) is spoken, showing a clear downward trend of Taigi-usage across generations.

He believed a major reason for the seeming revival of Taigi usage in recent years can be attributed to its circulation on the internet. Perhaps by chance or by amusement, certain Taigi songs, dramas, and articles perforated the digital filter bubble of Taiwanese netizens. However, Taigi’s current rise in popularity does not necessarily indicate that the language is being revitalized. Many young people will appreciate and may even come to adore contents produced in Taigi, but when they return to their everyday lives they lack the sufficient opportunities and incentives to study Taigi. Yap likened such people to those who “won’t play ball games but like to watch people who can play it well.”

First and foremost, language learning begins in childhood education. Many parents begin speaking to their children in Mandarin when they are at a young age to prevent them from falling behind in school. Because Mandarin is the dominant language in Taiwan, it is a core subject for children in school – not Taigi. Many grandparents follow suit by speaking to their grandchildren in choppy Mandarin. Now, Taigi-language competitions are popping up to incentivize high school students to study the language, providing them with credits in college entrance interviews. While these students study diligently, “they can’t speak beyond a sentence or two during the interviews. There is a total disconnect between their competition training and everyday life,” said Yap.

According to Yap’s research from “The Impact of Family Language Use in Childhood on Education and Career Prospects” (幼時家庭語言對教育與職業取得的影響) based on Academia Sinica’s “Taiwan Social Change Survey” (台灣社會變遷基本調查), he emphasized that when considering the parents’ level of education and socioeconomic status, family language use in childhood had no significant impact on children’s academic achievement.

If local languages in Taiwan are on the decline, how can Taigi be effectively revitalized? Gustave Cheng provided three policy initiatives: promoting PTS Taigi, forming Taigi-language committees, and establishing Taigi schools. Yokita Lim encouraged people to integrate the use of Taigi into their daily lives, but without demanding Mandarin-speaking persons to speak Taigi. Speaking Taigi in everyday life is more essential. There is also no need to nitpick the pronunciation or word choice of Taigi-speakers who are struggling with the language, because doing so may ruin their language learning experiences.

When observing the larger trend of Taigi revitalization, Lu Dong-shi optimistically believed that the movement continues to improve step by step, despite at a slow pace. In the 1990s, the New Taiwanese Song Movement revived the Taigi language through musical productions. With the help of social media, not only has Taigi music gained popularity; now Taigi is also being taught in classrooms with both Chinese characters and romanizations. Other relevant course offerings are also now available. Taigi publications and literature are also gaining recognition, creating a greater push for the production of written works aside from musical productions.

Lu emphasized that instead of reviving Taiwanese, what he wanted to see is the integration of Taigi into everyday life. In this way, it will be easier to use Taigi for performances, pop-science, arts, and entertainment. PTS Taigi was initially created to teach culture, not the language itself —culture must be passed on and disseminated through language. The spirit and wisdom held within culture emerges through language, and only by teaching language can the cultural heritage be sustained.

PTS Taigi had just its one year anniversary [in 2020]. Lu reflected that his expectations have been met. The original idea was to build an audience base by first attracting older Taigi-speaking populations, from which they have already seen definite results. In the future, they look forward to more robustly targeting internet communities to attract younger viewers.

Flexibility and tolerance are key to Taigi revitalization. Supporters of Taigi revitalization are not trying to replace Mandarin with Taigi so that the latter becomes the most widely spoken language of Taiwan. Instead, they yearn for a time when Taigi-speakers can freely speak their language without facing discrimination or rejection.

At the end of 2018, the third revision for the “Development of National Language Act” (國家語言發展法) was passed, seeking to safeguard and secure the inheritance, recovery, and development for all natural languages and sign languages used by each ethnic groups in Taiwan.

As time passes day by day, Taigi revitalization feels like the prodigal son who drifted away in EggplantEgg’s hit-song “Back Here Again”. Will this recent wave fade away or pave the way for the return of Taigi? The data compiled regarding Taigi usage in Taiwan’s 2020 Census (人口普查) and the “2023 Taiwan Social Change Survey” (台灣社會變遷基本調查) may provide an answer.

※ Note: Taiwanese Hokkien, Taiwanese Hakka, and various local languages are all spoken and have a degree of official status in Taiwan. The labeling of any language in Taiwan’s multilingual landscape as “the” Taiwanese language continues to be a source of controversy. In this article, we adopt the mainstream usage of the term “Taiwanese language”, also known as “Taigi”, to refer to Taiwanese Hokkien. This choice does not represent our stance on the issue – we look forward to the robust development of Taiwanese Hakka and other local languages of Taiwan.

(To read Chinese version of this article, please click: 台語正潮?流行文化領頭後,台語能走向正常化嗎?)

用行動支持報導者

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

你的支持能幫助《報導者》持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,邀請你加入 3 種支持方案,和我們一起推動這場媒體小革命。