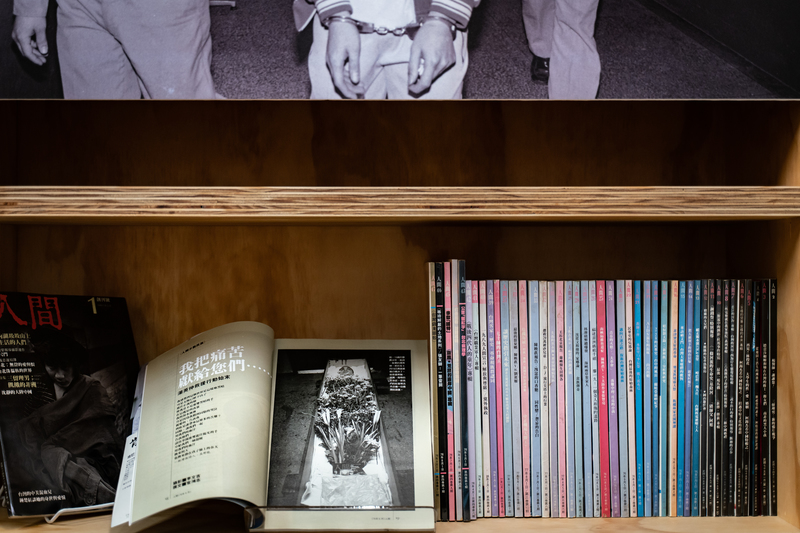

Though short-lived for just less than four years, the Ren Jian (Human World) magazine, founded in 1985, was like a legend, shedding light on countless dark corners of Taiwanese society and revealing the wounds of the land in Taiwan before and after the lifting of martial law. With its powerful photographs and writings, it defines the core of in-depth investigative reportage. For more than 30 years, Ren Jian has been mentioned every now and then, commemorated through various exhibitions, conferences, or awards, including the Outstanding Contribution Award bestowed by the 2021 Taiwan International Documentary Festival (TIDF). The Reporter meets with former Ren Jian employees and interviews them about their personal perspective of what the magazine means for their lives and for the era.

Things were heating up in Taiwan during the mid- to late 1980s (1985-1990). In terms of growth, not only had the agriculture-based economy of Taiwan transitioned into an export-led ODM economy; foreign commerce was also on the rise, with stock market indices multiplying 11 times over four years—hence the popular saying of the 1980s, “The Taiwanese are up to their ankles in money” (台灣錢淹腳目). Politically, with the waning of the international Cold War, the long-standing restrictions and censorship under the Kuomintang (KMT) rule was lifted in the years that followed. This included the lifting of martial law, the elimination of the ban on organizing political parties, the opening of cross-Strait family visits, and more. Taiwanese society witnessed a series of unprecedented changes.

Before the internet became widely available in the late 1980s, mass media was a mirror which reflected the reality and desire, voices and dreams of the Taiwanese public. The non-partisan (often transliterated as tangwai) magazines had already sprouted up during the martial law period, while the mainstream media flourished after the ban on newspapers was lifted in 1988. Amid the kaleidoscopic images reflected on the mirror, Ren Jian was like a huge shadow cast by the dark underbelly of the prosperous society of the times:

People making a living on top of garbage heaps; the indigenous people from eastern Taiwan who lingered at the margins of the cities; the mentally ill patients locked up by their family in the remote mountains; a veteran marrying mute women, working on farms at the Zhuoshuixi banks; the mixed-race children abandoned by American GIs during the Vietnam War . . .

These captivating, otherworldly landscapes, portrayed by highly contrasting black-and-white photos and literary renderings, directly present the situations of the underprivileged in a wounded landscape. These images sent a shock wave among young readers thirsty for new knowledge and for real-life depictions of the lower class. Starkly earnest photographic and literary styles have since become Ren Jian’s trademark.

The stories and issues that Ren Jian covers not only move readers at the level of sympathy and pity; they also restore basic human dignity to those underprivileged lives that had been abandoned, ostracized or else outright eliminated by mainstream society. This editorial direction was due in large part to the care and devotion of Chen Yingzhen (陳映真), founder of Ren Jian and a modern novelist. He proofread and revised nearly every draft, giving it a uniform quality.

“Shedding light on the people and the land that had been ignored or sacrificed during social developments have been a focal point of Ren Jian’s editorial practice,” says Liao Chia-chan (廖嘉展), chairperson of the Newhomeland Foundation (新故鄉文教基金會). “Ren Jian raised more awareness for the land, enlightening an entire generation of youngsters who are now in their fifties.” Liao joined Ren Jian and became a journalist after college and military service. His wife, Yan Hsin-chu (顏新珠), also worked there as a photojournalist.

“In hindsight, amid the postwar martial-law regime and the rapid rise of the economy, Ren Jian boldly reflected on and confronted reality. Through its photographic lens and literary gaze, Ren Jian guided the social values of an era. Universal values about the well-being of humanity were its core essence. In our current era of information overload, this spirit remains invaluable and invites further reflection.” Informed by their own experiences at Ren Jian, Liao and Yan kept recording local stories when they were later based in Puli. They established a sustainable eco-friendly village with the local residents who were affected by the 1999 Jiji earthquake.

In addition to presenting the lower social strata in a warmer, more humane light, Ren Jian’s ambition was not so much the documentation of objective truth, but rather an active intervention in the society. This aspiration culminated at Ren Jian’s reportage of the Tang Ying-shen (湯英伸) case. From a news item that was relegated to the margins of society, the Ren Jian reporters sought to reconstruct the life trajectories of Tang by visiting his hometown in Ali Mountain, attending court investigation and verdicts of his case, interviewing his classmates at National Chiayi Normal College, and traveling with his cremated remains back to his hometown, Tefuye. The stories acutely point out the prevailing structure which was complicit with this horrid homicide; namely, a Han-dominated society which had allowed discrimination and oppression to continue without addressing these problems.

This series of news coverage triggered public attention. Religious leaders, cultural workers, and indigenous rights activists put in collective efforts to launch a rescue campaign for Tang, who had been sentenced to death. They even wrote an open letter to President Chiang Ching-kuo (蔣經國) at a time when Taiwan was still under the martial law. After Tang was executed, they further facilitated dialogue and reconciliation between the two families affected. Before “restorative justice” was a concept, Tang Pao-fu (湯保富), father of the murderer, and Peng Ah-sheng (彭阿升), father of the victim, embraced each other, teary-eyed. Each promised to the other that they would “definitely drop by to have a cup of tea” when visiting Taipei or Ali Mountain.

The case of Tang Ying-shen was just one example of how Ren Jian aimed more than just to cover social issues from the sidelines. In the turbulent late 1980s, Ren Jian was involved in most social movements of the day, and in some cases even led them at the forefront. Those campaigns were deployed aganist a range of issues, including child prostitution (反雛妓運動), deforestation (搶救台灣原始森林), the constrution of a titanium dioxide plant by the US-based company DuPont in Lukang, Changhua (彰化鹿港反杜邦), the construction of the CPC’s Fifth Naphtha Cracker Plant in Houjin, Kaohsiung (高雄後勁反五輕), and the environmental movement against LCY Chemical Corp in Sui-yuan Village, Hsinchu (新竹水源里民圍堵李長榮化工).

“An ordinary magazine or media outlet could not have assisted local residents in protest,” says Fan Chen-kuo (范振國), former Ren Jian executive editor. Fan was a former high school teacher in Taichung. Through the introduction of his college seniors Chung Chiau (鍾喬) and Kuan Hung-chih (官鴻志), he was touched by Chen’s ideal and decidedly left his comparatively stable teaching post to join the anti-DuPont campaign in Lukang—a crucial starting point for Taiwan’s environmental campaign. Afterward, he was invited by Chen to join the Ren Jian editorial board. The 20th issue, titled “Tang Ying-shen Comes Home” in boldface, with Tang’s sister tearfully holding Tang’s ashes in hand, was entirely edited by Fan. “From the planning process to action-taking . . . we practically participated in the movements alongside local residents,” says Fan. “Later, during the anti-naphtha cracker plant campaign in Houjin, its organizers wanted to learn [protest] strategies from us. We also helped with organizing self-rescue organizations in the campaign and wrote slogans together. My later relationship with Chen Yingzhen was unlike his relationship with other reporters. Perhaps he’d wanted me to put my anti-DuPont campaign experience in practice, getting involved in more social reforms.”

Despite its short run (less than four years, from the inaugural issue in November 1985 to the last issue in September 1989), Ren Jian still left a deep imprint on Taiwanese society before and after the lifting of martial law. Although more than thirty years have passed, Ren Jian is still an occasional topic of discussion, being commemorated during various exhibitions, conferences, or awards every now and then.

Unfortunately, as the experience of reading on-screen rapidly replaced that of reading in print, age-old hard copies of the magazine became hard to come by. With the exception of those who purportedly request them at the National Central Library or search for them at used bookstores, fewer and fewer readers have actually read coverage from Ren Jian. For those who were born in the internet age or even around 1980 and are now entering middle age, they no longer know who Chen Yingzhen or what Ren Jian was. Ren Jian has almost become a legend that many have heard of but never seen.

“I have never really caught up with him, but he had been left behind by the times. His was like a utopia we’ve never seen, but have already grown tired of.”

This is the ending of contemporary Chinese writer Wang Anyi’s (王安憶) “Internationale”, a prose essay in memory of Chen Yingzhen. In 1983, she followed her mother, Ru Zhijuan (茹志鵑) to participate in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in the U.S. She first met Chen, who was also invited there. The course of their conversation inspired the then-fledgling writer Wang Anyi.

Using the 2021 TIDF Outstanding Contribution Award as a point of departure, The Reporter interviewed four former Ren Jian journalists who served in different roles at Ren Jian. The aim is to take readers back to the scenes of their first reports published in the magazine. From these works, they reflected on what Chen Yingzhen (or more intimately referred to as “Old Chen”) and what Ren Jian meant to their lives and to our time. The following interviews are narrated from the first-person perspective.

Tsai Ming-te (蔡明德), former Ren Jian photojournalist and illustration editor, later manager of photography of Capital Times (《首都時報》), Liberty Times (《自由時報》), China Times (《中國時報》), and China Times Weekly (《時報周刊》). Author of Scenes from the Human World: Documentary Photography in the 1980s (《人間現場:八○年代紀實攝影》).

First report in Ren Jian: “The Small World in the Neihu Garbage Mountain,” in “Human World Environment,” published in issue 1, November 1985.

My first topic was on the “garbage mountain” in Neihu. Having only read from newspapers about garbage collectors there, I was quite shocked when seeing a mountain full of people. As long as you did not fear the squalid and stinky environment, with just a basket, a bamboo hat, a pair of rain boots, you could also collect waste. When I arrived there, I didn’t know how to photograph or write a report—from an environmental perspective or even from a human-centered perspective. After taking some random shots for a while, I naturally felt that the people should be at the center, while the environment was of secondary importance.

Old Chen always told us: “Make ‘the people’ your focus! Don’t worry about not having stories to write. Love stories have been written for thousands of years and there’s still more that can be written about. The only thing you need to worry about is not going out to look for stories, or not knowing how to tell them.” I worked really hard. I felt like even if I failed the first couple of times, Chen Yingzhen would encourage me to keep returning to the scene if I didn’t have enough materials. Going on-location was where you really honed your skills and grew.

In 1982, I just graduated from the Department of Journalism at Chinese Cultural University. Initially, I secured a post at Liberty Daily (《自由日報》; present-day Liberty Times). Back then, newspapers were only three large pages long. The senior journalists had already filled up the posts and demands for photojournalists were scarce. On average, only two posts were needed at each agency. Meanwhile, I saw that another communication agency was looking for photographers. After I applied, I was surprised to learn that it was founded by Chen Yingzhen! I had heard of this person in university. Our literary reportage course instructor Kao Hsin-chiang (高信疆), who was an important supplement editor, took us to a reception held in Rongxing Garden (榮星花園) for Bo Yang’s (柏楊) welcome party. He had just been released from prison. Chen Yingzhen was also there. It was then that I vaguely knew that he also served his term before the Formosa Incident (美麗島事件). Then I was curious to read his books.

Shortly after having a job interview with Chen, I decided not to take the post at Liberty Daily, though Chen only paid me slightly more than 10,000 TWD (264 USD) at Ren Jian, and basically my salary remained the same until the very end. Li Wen-chi (李文吉) and Fu Chun (傅君) worked there earlier than I did—they were work cronies during its founding moments. Since Chen worked at an American pharmaceutical company and had connections there, at the beginning, he did a PR magazine for the pharmaceutical company, but he turned all front cover stories into humanistic reports. In 1983, Chen was invited to the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. Perhaps he read many Western photojournalist works and was heavily influenced by them. Not long afterwards, he said: let’s create a magazine “centered on humanity.”

Nobody knew how to create a magazine, so we spent almost two years preparing. We went about taking photos after group meetings. Sometimes we did it on our own, not knowing exactly what to do. For example, I once took photos of the First Children Development Center (「第一兒童發展中心」) , which was the earliest institution for the mentally challenged. I left behind a lot of negatives, which are quite precious documents, but I didn’t know what to do with them. It’s a shame that they weren’t turned into written reports. At the beginning, Chen Yingzchen asked a lot of established photographers, such as Juan I-jong (阮義忠) , Chang Chao-tang (張照堂), Liang Cheng-chu (梁正居), Wang Hsin (王信), and others to comment on our pictures. Once the trial issue came off the press, they gave us the green light, and so we hit the road.

The front cover of the trial issue features the picture I took at the garbage mountain in Neihu. Only 5,000 copies were printed. Someone borrowed it from me, so now I don't have a copy either. Back then, Guan Xiao-rong (關曉榮) just quitted the job at a mainstream media outlet and threw himself into photojournalism. He returned from Bachimen, Keelung, with a set of photos. Chen Yingzhen didn’t know who he was, but decided to publish his photos and use one as the front cover of the first issue. To this day, I still often complain to Guan that my front cover was hijacked by him.

Chen Yingzhen was very insightful. For instance, when students launched the Love of Freedom Movement (自由之愛) in response to the punishment of the College Journalism Society (大新社) at National Taiwan University, he summoned me to his office and asked me to document the student movements in Taiwan which would be on the rise. Therefore, I followed the movements quite closely from the start. Once, Chen took me to attend Yang Kui's (楊逵) funeral and asked me to visit the disciples of Huang Shun-hsing (黃順興), a prominent figure in the non-partisan movement and a forerunner of the environmental movement in Changhua. According to Huang, during the period when there were mass poisonings by polychlorinated biphenyl, funerals were held every other week in the village. Those who didn’t die were blinded, leaving behind tremendous aftereffects. Nobody dared to marry the villagers. Those who left were gone completely; not a trace of suffering was left behind. Chen lamented that after such a big catastrophe very little news coverage remained. Things lie in the hands of Ren Jian.

From food security to the environmental crisis, there are still so many problems in Taiwan after all those years. It’s like the recent controversy over algal reefs in Datan. Back then, we went there to conduct an interview about cadmium pollution in rice. Later, it turned out that the government purchased the land to build a power plant. It’s ridiculous that the ones who caused pollution were at large and didn’t even have to serve prison terms! Kuan Hung-chih and I carried backpacks and took one bus after another to Datan Village. There wasn’t even a noodle stall. Relying on instant noodles and vegetables purchased from the carts, we cooked one meal per day, and stayed there for over ten days or so.

Kuan Hung-chih’s questions were detailed, and so was his note-taking. He graduated from the Department of Foreign Literature at National Chung Hsing University. He knew Chen Yingzhen from very early on and was very close to Yang Kui. When the Tang Ying-shen incident happened, Huang Chun-ming (黃春明) came to our office to describe it. Not knowing anyone, Guan and I went straight to Tefuye in Ali Mountain the very next day and found Tang’s mother, who walked on crutches because of a car incident. We stayed at the Tang’s when we went to interview her three to four times, until Tang was executed the next year.

Ren Jian’s first ever report to directly bring up the White Terror—which was probably also a first for all of Taiwan media—was about “Warrior Tsai Tieh-cheng” (〈戰士蔡鐵城〉), an underground communist member executed in the 1950s. It was also written by Kuan Hung-chih. At that time, Chen Yingzhen took us to Dajia, Taichung, to visit Kuo Ming-che (郭明哲)—whom we referred to as Old Kuo—who had been involved in the Dajia Incident (大甲案) during the White Terror. I still remember that his old brick house was full of books. We knew nothing about it before that, and that was the first time we got in touch with a real-life underground communist. A group of us went together. Among them, Lan Bozhou (藍博洲) was so weakened by diarrhea that he couldn’t walk and stayed behind. We joked about him being poisoned by the underground agent. It turned out that Lan chatted a lot with Old Kuo. Later, Lan threw himself into the writings about the February 28th Incident and the White Terror, which was influenced by that experience.

What I remember most vividly is that Liu Ke-hsiang’s (劉克襄) father, Liu Wan-shou (劉萬壽), who also participated in the organization but wasn’t ratted out. We drank with him in a night market. Upon talking about how well Tsai Tieh-cheng (蔡鐵城) treated them and taught them how to read, he burst into sobs. We later took him back home, but didn’t include his story in our report. It was still during the martial law period, when those who were still alive should not be exposed.

Kuan, who reported on so many special topics, disappeared later. None of us could reach him. Lai Chun-piao (賴春標), who wrote a series of reports on rescuing forests in Taiwan, didn’t keep in touch with us, either.

Lai’s reports were a wake-up call to the reality of deforestation in Taiwan and played an important role in the forest protection movements. He only held a high school degree and was very candid. He liked to climb mountains and take photos, always in his military boots. One day, he came to the Ren Jian office with a pile of photos taken in the mountains. He told Chen that deforestation was a grave problem and asked if we should do a report. Those photos were finely mounted onto cardboard and have remained at my place in Taichung. Chen said that the photos were beautifully taken, but he couldn’t tell there was any deforestation. So he asked Lai to work for Ren Jian and continue to document the issue up there in the mountains. Lai said that he didn’t know how to write, and Chen told him that he would once he came to work. He took pains to write but he worked very slowly, always writing in the office until daybreak.

It was very difficult to work on this topic. One has to be able to climb mountains, take photos, analyze data, survive the wilderness, and even run the risks of being hounded by illegal lumberjacks. None of us photographers were capable of these, except for Lai. It can be argued that the Ren Jian forest series spearheaded two large-scale marches to call for forest protection, which directly influenced the logging bans put into place later. Once, the Head of the Forestry Bureau (林務局) replied to Ren Jian, in calligraphy. Then, the prosecutor asked Lai to lead the way into the mountains and revealed that the Forestry Bureau was just putting on a show.

Shortly after the Jiji Earthquake, when I was taking pictures in Fengyuan, someone tapped my back. I turned my head and saw Lai. Coincidentally, Chen Yingzhen made a call, asking me if everything was okay in Taichung. I told him that things fell in my place but my family was fine. He asked me to “keep good records.” Chen Yingzhen still cared about us. That was the last time I saw Lai Chun-piao.

Over the past few years, some people have contacted me through Facebook. They thanked me for keeping records of their family members who appeared in my photos. For example, a son of a miner took his son to a library exhibition and chanced upon a photo I took 30 years ago, which was taken exactly at the moment where miners were exiting from a minefield. Since miners would clean themselves up before returning home, he had never seen his father like that, so he went back to confirm with his mother and aunt.

In his letter, he specifically mentioned that, amid a series of mining accidents in the 1980s, his family was always on tenterhooks. Many miners died early of pneumoconiosis. Back then, he didn’t understand why his father drank all the time, until he grew old enough to understand his father’s hard work. His father passed away a year before he wrote to me. My work isn’t some masterpiece and didn’t influence many people, but the power of realism enabled a miner’s son to recognize his father 30 years later. It is worthwhile for my work to receive such a warm response and bring about reconciliation.

Chichi (季季), born Li Jui-yue (李瑞月), entered journalism in 1977 and was invited by the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in 1988. She served as the editor of the supplement for United Daily (《聯合報》), the editor-in-chief of the supplement, “Human World”, for China Daily (《中國時報》), deputy editor-in-chief for China Times Publishing (時報出版), contributor for China Times, and editorial director for INK Literature (《印刻文學生活誌》). She published more than 30 novels, essay collections, and biographies.

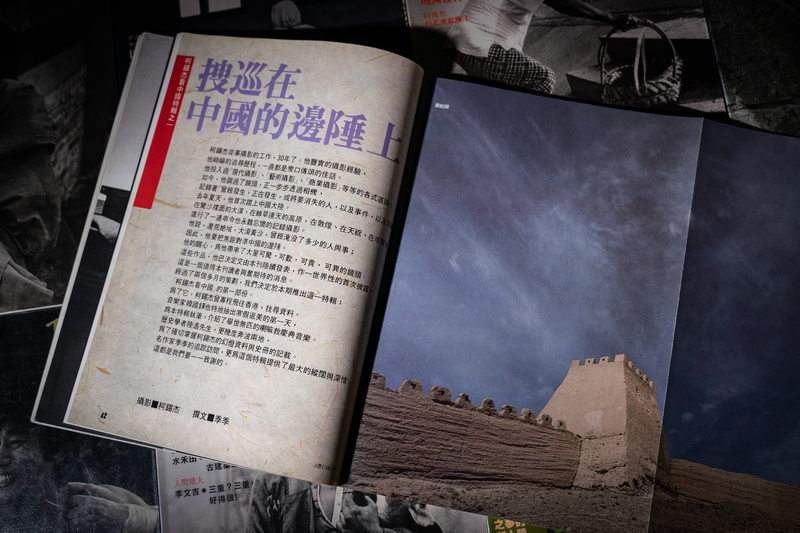

First report in Ren Jian: “On Patrol at China’s Border”, in a special section on Ko Hsi-chieh (柯錫杰) on China, in issue 5, March 1986.

I might have been Ren Jian’s only “volunteer.”

Those memories have been sitting at the bottom of memories for so long that I’ve almost forgotten. Last night, I dug out all my Ren Jian magazines to count the issues I was involved in. The first report was in the fifth issue of 1983, where I interviewed Ko Hsi-chieh (柯錫杰) and wrote about “sunning the Buddha” in Tibet. Ko took a series of photos in China, which was a thrill when cross-Straits visits weren’t permitted yet. My last piece was in the fourteenth issue, in which I did an oral interview with Lai Chun-piao about the giant trees he discovered in An Tung Chun. On other occasions, I mostly helped with proofreading and recording.

I participated in Ren Jian for two reasons: first, Chen Yingzhen asked Kao Hsin-chiang to be the editor-in-chief. Kao, who used to be my superior when I worked for the “Ren Jian supplement” in China Times, asked me to help. Second, under the surveillance of the Garrison Command, my ex-husband Yang Wei (楊蔚) helped monitored and reported the activities of Chen Yingzhen’s “Democratic Taiwan League” (民主台灣聯盟) reading group in the 1960s, causing them to be arrested and imprisoned (the details of which could be found in Walking Trees (《行走的樹》). Out of guilt, I “volunteered” for Ren Jian.

I mostly waited until after the newspaper finished reprinting at 10:30pm to go to Ren Jian’s office on Heping East Rd. Thus, when I arrived, it was already very late at night. Seldom would I meet Chen Yingzhen and the other colleagues. There would only be me and Kao, who was also used to working at night.

When Kao Hsin-chiang served as the chief editor, he started a column called the “Margins of Reality” (「現實的邊緣」) in the “Ren Jian supplement.” Since then, and for the first time in Taiwan, photos began to reflect reality and written reports began to address social issues in ways that differ from previous social news. Previously, newspaper supplements mostly featured prose, new poetry, and fiction. Under Kao’s leadership, the genre of reportage began to appear and the China Times Literature Prize reportage prize, which once invited Chen Yingzhen as a juror, nourished some writers. Besides, he was deeply influenced by mainland Chinese reportage literature. All of these factors led him to found the Ren Jian magazine.

More crucially, it was related to the murders of Lin Yi-hsiung’s daughters (林家血案), Chen Wen-cheng (陳文成), and Jiang Nan (Liu Yi-liang; 江南) that happened shortly after the Formosa Incident. Due to political reasons, the media could not cover many taboo subjects. All of this was a thrill for him. Whether or not the press had the freedom and courage to report became the crucial factor that made him decide to found his own magazine. There were two important reports in the Ren Jian magazine about media coverage. One was the founding of The Journalist (《新新聞》) in 1987, and another was the special interview with Yen Wen-shuan (顏文閂), editor-in-chief of Independence Evening Post (《自立晚報》). The two major newspapers at the time would not cover the Taoyuan International Airport Incident in which Hsu Hsin-liang (許信良) attempted to enter Taiwan. Only Independence Evening Post published reports on the incident and the military and police brutality that ensued. This special interview exhibits Chen Yingzhen’s insistence on criticism.

Whether writing news reports or fiction, Chen Yingzhen remains forever critical. His words are succinct and exquisite, and the critical attitude was his most important spirit. From the 1960s to the 1980s, for about three decades, he was a real cultural giant in Taiwan. From then on, nobody could catch up with him even to date. His criticism was done not only through fiction but also through his actions. There was no other writer like him; he wasn’t just confined to his den with his writing, but instead he actually went out into the world, reaching new heights through Ren Jian’s reporting and activities.

Later, his pro-unification stance became more and more conspicuous (Chen Yingzhen founded the Chinese Unification League (中國統一聯盟) in April 1988). Amid the nativist trend in the Taiwanese society, the general public’s attitude toward him changed from holding him in awe to something different. The ideological clash between the unification and independence factions unfortunately overshadowed his literary accomplishments. For years, he was unwilling to receive official acknowledgments. Once, the person in charge of the National Award for Arts (國家文藝獎) called Chen Yingzhen to ask him to confirm his participation in the award ceremony, which symbolizes the top honor in our cultural field. After Chen Yingzhen finally agreed, in the end, some in the jury dismissed him for being “pro-unification.” In the end, he didn’t get the award.

In hindsight, out of all the media outlets, only the Ren Jian magazine was willing to excavate many important environmental issues—for example, the Garbage Mountain reported in Neihu in the November 1985 inaugural issue. The problem had existed for more than ten years, but the average person only knew that it was a mountain of filth. Nobody was willing to investigate the effects that extended from the bottom of the mountain. Only Ren Jian conducted such a report that covered land and water pollution and the impoverished commoners who relied on the garbage mountain to eke out a living. The garbage mountain was an important symbol, bringing to light the actual circumstances of Taiwan at the time.

Chung Chun-sheng (鍾俊陞) was a photojournalist for China Tide (《夏潮》) and Ren Jian, once opened a bar near National Taiwan University, co-founded a factory with Chen Yingzhen, and followed Chen to his last days.

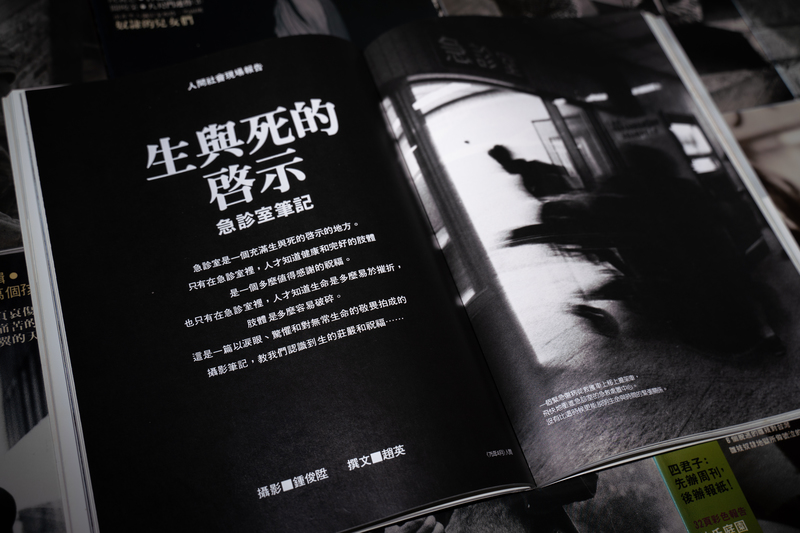

First report in Ren Jian: “The Moral of Life and Death—Notes from Emergency Room”, no. 6, April 1986.

My first interview was a failure. I didn’t know a thing at the beginning, so Chen suggested that I start with what I was the most familiar with. “Where is your hometown?” “Pinglin,” I said. “Go back and start taking notes,” he said. I took from geology, climate, human culture, and every other aspect I could find and put it all in. It was as if I were working for National Geographic. But I ended up getting lost at sea. My report was pointless and I didn’t have the skillset to edit and organize my materials. In the end, the report wasn’t published. Then, since Chen used to work for Sterling Winthrop, Inc., which had a lot of contacts with the medical profession, I wanted to photograph the scenes from the margins of life and death in the emergency room, but after staying in the emergency room at MacKay Memorial Hospital for three months, I couldn’t submit my report. “Why?” Chen Yingzhen asked. It was because whenever I went there, I was reduced to tears. Helping direct the family members to the sickbeds and taking them to the mortuaries, I was unable to detach myself. Through blurry eyes, I couldn’t tell what was in front of the camera lens. It took me a good few months to finally get my first article out.

Chen was very kind; he never scolded us for failing to submit articles after several months. He was always gentle when giving his opinions; if the draft fell short, he would keep revising it down to the punctuations. Once, he made a meaningful remark—now that I think of it, I regret not having seized the opportunity—he said, “You should cherish the Ren Jian magazine. Once it stops operating, there will no longer be another magazine like this that gives you so much freedom. Here, you can find your own topics and do whatever you want, and nobody will bother you.”

What kind of magazine was Ren Jian? To answer this question, we must first define what kind of person Chen Yingzhen was. The two are inseparable. He was a thinker, a novelist, and an artist. His identity was complicated. He was also a political figure, not just simply a literary figure as he appeared to be. Studying him is a huge and brain-wracking task. In 1957, he participated in the May 24th Incident, the largest anti-US protest (劉自然事件) during the martial-law era. In 1968, he was involved in the Democratic Taiwan League case (民主台灣聯盟案) and was imprisoned. After he was released in 1975, he immediately began to intervene in the Taiwan nativist literature debate (鄉土文學論戰) and put forth a blaring slogan to define what literature is: “Literature originates from, and reflects, the society.” What he wanted to do from the beginning with the Ren Jian magazine was definitely not to merely create a literary magazine.

He cared deeply about our research and learning of the social characteristics of Taiwan, noting that we should first study in-depth and learn about the problems facing Taiwan before knowing how to interview and report. During the White Terror era in the 1950s, postwar Taiwanese society was nurtured by the United States: Taiwan constituted part of the U.S. island-chain in the Pacific, a strategic formation used to contain communist China. Under the straitjacket of martial law, Taiwan’s economy rapidly grew. In the 1980s, when Taiwanese economy prospered, the public started to become aware of the issues of environmental protection, nuclear power plants, industrial pollution, laborers, the indigenous people, human rights, and more. There was also a variety of turbulent protests and fiery demonstrations. At this moment, in 1983, he was permitted by the government to leave Taiwan for the first time to participate in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. There, he interacted with many writers from the Third World, which had a huge impact on Chen. He thought it was time to found this magazine after returning to Taiwan.

The opening statement of the inaugural issue mentions faith, hope, and love (“Because we have faith, we have hope, and we have love . . . ”). Some interpreted it from the Christian perspective, but in my view, this was to use the language of humanitarianism to cover up Marxist thinking—which could not have been openly expressed. But that was how Chen got involved on the battlefield. Readers would not feel that we were too radical if we present literature and art to them. This distinguishes Ren Jian from many political commentaries of the time. For instance, China Tide (Xia chao;《夏潮》), a left-wing non-partisan magazine, was dedicated to political commentary in which Chen also played a vital role. But he made a clear distinction: Under the cover of literature and art, Ren Jian was more readable and more impactful. Every single piece pointed out a crucial question of the society.

I was asked by a friend to go visit Yang Kui and I took a few photos. China Tide thought these photos were quite good, so I was invited to become a full-time photographer. That was how I met Chen, who took me to join the earliest founding committee. I fumbled my way into this circle. My role was different from my colleagues who focused on interviews. I often put down my camera and helped out with organizing, for instance, the anti-refinery protest in Houjin, the urban indigenous people's protest in Xizhou tribe in Xiaobitan, Xindian, and the indigenous ‘Shell-less Snail Movement’ (無殼蝸牛運動) which focused on housing precarity.

After Ren Jian ended due to financial difficulties, Chen Yingzhen actually thought about re-starting. To raise funds, I went to serve as the general manager for the then-biggest lamp set manufacturer in China to manage various departments after being recommended for the job by a friend of his. At that time, there were about 9,000 employees in the factory. Before long, however, I found out that the Taiwanese owner treated the workers like slaves. Of course, I sided with the workers and fought for the working conditions they deserved. In the end, I fell out with the owner and left. Chen Yingzhen and I rallied some workers to establish another factory, trying to build the best working and living environments for the workers. But our efforts were always contained by that Taiwanese owner in one way or another. We failed in the end and had to close the factory we had run for two years. Therefore, the plan to re-issue Ren Jian became out of reach.

In 2006, because he served as a guarantor for his younger brother’s printing factory, his house was foreclosed, leaving him with close to no property in Taiwan. Coincidentally, Renmin University in China invited him to be a visiting professor. Before departing, he promised me that, in two years, after he returned, we would carry out our plan together once again. Unexpectedly, before his classes could even start, he suffered from a stroke. In Beijing, Chen’s wife and I were there with him when he was undergoing surgery. In the last days of his life and medical treatment, I also often went to keep him company. In 2016, he passed away in Beijing. Together with Chen’s wife and family, we adhered to Chen Yingzhen’s last wishes and spread his ashes in Qinghai Province—the source of the Yellow River.

When he was bedridden, I played videos of his former colleagues and friends speaking to him at his bedside. After he suffered from a stroke, he lost part of his language ability and couldn’t clearly express himself. But since I have been close to him for a long time, and during the martial law period, some messages were conveyed through implications. So, with just a few words, I could already comprehend what he was trying to convey. But his wife would curiously ask me what he was saying.

Ren Jian was well-reputed but failed to sell; readers wouldn’t purchase it. A hundred TWD was too pricey for students, who often passed the magazine around or Xeroxed it. When we decided to stop running for the first time, Chen asked me to announce the news to our colleagues. After I finished, everyone was dumbfounded. Some claimed that they would work even without salaries. Dejected, I reported back to Chen, and we stuck with it for another while. After another half a year, the condition worsened. This time, I asked him to make the announcement himself. On that day, more than forty employees cried together as if they had lost a close relative.

After the announcement, Chen asked me to take him home. On our way to Xiulang Bridge en route to Zhonghe Rd, he sat on the passenger seat and looked outside the window, teary-eyed: “Everyone has a family to raise. They cannot live without wages.” Although quite a few potential patrons expressed their willingness to support the magazine, he refused all of them. We spoke privately about this. He said, “Chung, if you invest your money in me, it might be okay if we lose money on the first few issues. After three or four more issues, the investors might say, ‘How about having something juicy?’ Then what are we going to do?”

To keep our independent character, we don’t take financial aids. It has always been that way. In the past, we never took awards from the government. Chen once said, “I was once your prisoner. How can I be your honored guest today?” Like Chen’s wife, my attitude toward the TIDF Distinguished Contribution Award is not to accept it. If Chen were still here with us, I believe he would still insist on his original intent when founding Ren Jian. He would critique social injustice and the state apparatus from the underprivileged people’s perspectives.

Tseng Shu-mei (曾淑美), former assistant editor of Ren Jian, journalist. Later worked in advertising companies. Former Executive Creative Director of the world’s largest advertising company, McCann, in Beijing. Published poem collection A Girl Fallen in Flowers (《墜入花叢的女子》) and Sorrowlessness (《無愁君》).

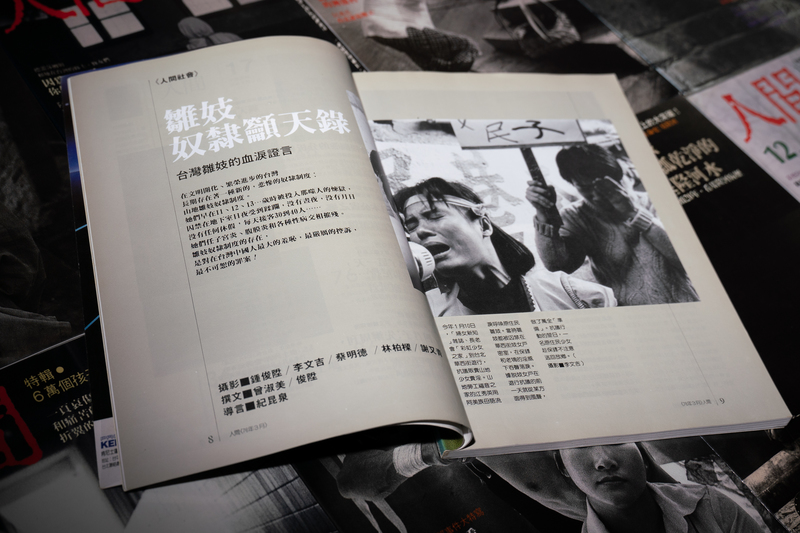

First report in Ren Jian: “The Enslaved Prostitute’s Call to Heaven—The Bloody and Teary Testimonies of Child Prostitutes in Taiwan,” in “Human World Society,” published in issue 17, March 1987

In 1987, I wrote a poem titled “Remembrance” (〈紀念〉), and my mind was full of the view of the alley where the Ren Jian office was located:

On the plain, the masses did not appear Our sky is flogged by thunder and lightning, deconstructed Dreams and hardships, the rain pours and the snow falls I am ordained on the eve of despair by the remnants of warm love Here I stand alone and silent On the snowy ground, where even sound is exhausted I fabricate various plots To relay a sentiment that is, after all, sincere.

I dreamed of becoming a writer when I was in college and read many of Chen Yingzhen’s fiction. I especially liked “The Comedy of Narcissa T’ang” (〈唐倩的喜劇〉) that analyzes intellectuals in Taipei, and the melancholic “A Couple of Generals” (〈將軍族〉). When the inaugural issue of Ren Jian came out, I was surprised that my idol founded a magazine. Leafing through the pages, I thought it was fantastic. I’ve never seen magazines like that.

All along, the education we received was very sheltered. No one in the entire country, in the entire system would encourage you to look closely at reality, to pay regard to the more disadvantaged. Ren Jian was like a bomb that shook the young people of the time. I quickly applied for a position, beginning as an assistant editor, running errands while observing how Old Chen revised the articles. Even just that, I had already learned a lot. After serving as an assistant for more than one year, he asked me to interview the child prostitutes who had just been rescued, perhaps because most of my colleagues were male.

When I first saw those teenage girls, almost all of whom had been sold more than once and pimped out countless times, they had just been rescued and given shelter. I was deeply shocked. At that time, all eyes were on the incident, but no one had done an in-depth interview with these girls. Limited by the traits and scope presented by the media, most newspapers could only cover the more tragic and dehumanized aspect of the incident. Indeed, they were very unfortunate and deserving of sympathy, but since the reports remained at a superficial level, the average reader wouldn’t picture them also as individuals, as girls.

I’ve been to Guangci Bo’aiyuan Park (廣慈博愛院), a workhouse which accommodated them, at least three times. I gradually took their stories back with me and wrote about them. Indeed, because I am also a woman, they felt more at ease around me. Also, since I didn’t have any theoretical training, I simply noted down what moved me most—that these girls were so miserable but still lived on. They were even able to joke with me, and they also had dreams not unlike other girls, like longing for a beautiful dress.

I treated them like people that were just like myself, without too much bias or presumption. I don’t like the journalistic practice of framing, that is, the way we represent our subjects within a certain framework, even if it came out of good intention or sympathy. It’s important for a report to present the person as a round character. Perhaps because of my preference, the report was overall well-received. Our colleagues would sometimes go somewhere nearby for a bite to eat after work. One time, Kuo Li-hsin (郭力昕), who briefly served as editor of illustrations for Ren Jian, told me that my report finely presents its subjects in a humanizing way without too much sentimentalism. It was a great encouragement for me.

In general, Chen trusted our on-site observations and the stories we brought back. He could easily tell how to adjust the articles to give them better contours. When he was revising our articles, he wouldn’t change the specific details of our stories. Instead, he might try to reframe the story in terms of theoretical issues. For example, we could find a critique of the slavery system in the opening paragraph in this report. This is definitely his work. The critical perspective that Chen used as an introductory remark gives a better focus to the story, underpinning its narrative with sociological concerns.

Old Chen was very approachable and was good at mocking himself. His pro-unification leftist politics was not welcomed in Taiwan. One day, a pro-independence friend ran into him at the airport, asking if he was going to Beijing again. He was like, yes, “Despite all its problems, I still love it nevertheless.” I’ve worked in Beijing and really couldn’t stand anything about the PRC. Why did a great person like Chen, who totally didn’t calculate personal interest, have such a huge blind spot, and ended up turning from leftism to parochial nationalism? This is a mystery to many. Out of deep love and loyalty, even pity feels like disrespect to us, so we could only remain collectively silent.

Beyond ideology, Chen Yingzhen was like a sun that attracted people with completely different styles to orbit around him: Mr. Tsai (Tsai Ming-te) was approachable. Li Wen-chi was humorous. Guan Xiao-rong had a fighting spirit. Kuan (Hung-chih) was so emotionally invested that whenever he came back from interviews, he broke into tears. (Lai Chun-) Piao was like an uncle but he wasn’t that old yet . . . Everyone was completely spellbound by his charisma. Chen’s speeches and words were so naturally crafted and deeply moving—maybe because his father was a priest. He was born with an ambition to make this world better.

I felt like Ren Jian was quite masculine a group. Men liked to deal with impactful, contentious events, like the Tang Ying-shen incident. Hearing the stories beside them, I was of course deeply shaken and moved, but found it hard to discuss the details with them. I personally prefer telling stories of people without referencing a pre-existing framework or strong opinions. For instance, I once interviewed a veteran in Bitoujiao whose wife was mentally ill. He didn’t know how to prevent her from running amok, so he tied her up like a dog. They kept a bunch of sheep and the landscape there was beautiful.

A highly idealistic group would compete internally over some notion of purity. If one came off as less than pure, she would be consciously or unconsciously criticized. Back then, I was like a little girl who wasn’t too serious and just wanted to be romantically involved, and was probably hurt a bit as a result.

In the last days of Ren Jian, I considered myself to not be a very efficient employee. Also, I had an unrealistic idea: if I switched careers to the more profitable advertising industry, could I come back after making some money and invest some of it back into Ren Jian, which had been struggling financially? Little did I know that once I switched to the Ideology Advertising Agency Ltd. (意識形態廣告公司), Ren Jian would suddenly stopped running. Ideology made a lot at the time. Our CEO Cheng Sung-mao (鄭松茂) asked how large Ren Jian’s deficit was. I heard from Chen that it was two million TWD annually. The number was inconsequential to an advertising company, but Old Chen always declined external financial support. Later, when other potential investors came to Chen, their offers were all declined.

Mr. Chen Yingzhen left Ren Jian as a tremendous legacy for Taiwanese society. Countless generations of young people were inspired by it. Sometimes, I am saddened to know that many people no longer know about Ren Jian and Chen Yingzhen, who were such a huge and taken for granted presence when we were young. I am only in my fifties but I am already witnessing its fading. The extent to which we should talk about this magazine differs depending on people’s individual opinions and personalities. It holds my affections. Despite guilt and self-limitations, I will keep telling the stories of Ren Jian out of a sense of responsibility to pass it down in our memories and histories.

2021 TIDF to Bestow the Outstanding Contribution Award to Ren Jian Beginning in 2014, the Taiwan International Documentary Festival (TIDF) established the Outstanding Contribution Award to honor excellent contributors for Taiwanese documentaries. In 2021, the twelfth award was bestowed on the Ren Jian magazine (1985-1989), founded by the late author Chen Yingzhen, to honor its pioneering influence on documentary image-making in Taiwan. The jurors maintain that Ren Jian focuses on social issues and the minority groups. Its reporters traveled to every corner of Taiwan bringing with them a realist perspective. In the 1980s, when freedom was limited, its strong humanistic concern and truth-seeking spirit provided important intellectual enlightenment to an entire generation of young people. Although written text and still-photography were their mainstays, every feature was like a “documentary on paper,” replete with humanitarianism and care for the underprivileged. Passed on from one generation to the next, it has been a driving force in the development of Taiwanese documentaries before and after the lifting of martial law, and thus has also shaped the tasks and aesthetics of the documentary genre. Before documentary filmmaking became widely popular, Ren Jian had already documented many issues using video recordings. Its subjects would later become the material of Taiwanese documentaries. Previous winners of the Outstanding Contribution Award, such as Green Team (綠色小組), Fullshot (全景傳播基金會), and director Ke Chin-yuan (柯金源) are just a few examples of people who were greatly influenced by these early productions.

(To read Chinese version of this article, please click: 重返人間──陳映真的烏托邦,與4位《人間》雜誌工作者的第一件差事)

用行動支持報導者

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

你的支持能幫助《報導者》持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,邀請你加入 3 種支持方案,和我們一起推動這場媒體小革命。