Chang Chaotang Interview──A Photobook is more than just a book

報導者(以下簡稱報):你是如何觀看一組攝影作品?對於不同型式的閱讀,你要如何去理解?

張照堂(以下簡稱張):一般來說,觀看有三種方式。

一個是你到展場看,在現場你可以仔細閱讀那些照片,如果展場很安靜的話,你還可以很自在的一張張看,仔細看每張照片的細微層次、細節,質感,拿音樂來作比喻,這好像去聽一場音樂會,因為現場,有直接的震撼或感動。

第二種就是看攝影集,它跟展覽會場不一樣,在展場裡你是被那個空間包圍起來,你被擁抱在那個氛圍;讀一本書,你是擁有它,拿到這本書你是可以隨時看、慢慢看,也可以跳躍著看、前後看、反覆看,仔細推敲它的編輯方式,可以有更多時間琢磨、比較。但是印刷品要與原作照片比較的話,就很難感受到攝影家的氣質、情感或氣勢了,這很像只是買一張唱片回家聽,跟你在現場感受很不一樣。

另外一種就是透過網路上看,因為載體的特性,它就是快速、輕便、容易攜帶,隔著螢光幕,它是透光的,影像看起來容易有三度空間的幻覺,色澤更艷麗,但它是片段的,閱後即過,印象不容易留駐,更不好連結。如果真要好好閱讀、研究攝影作品的話,我覺得印刷這個載體是較方便、恰當的,因為你隨時可以取閱,專心看、仔細想,它的取景、佈局,結構,以及起、承、轉、合的敘事性關係等等。相較於其他型式,攝影集的閱讀會讓人更容易有收穫。

報:你對如何去閱讀一個攝影作品有什麼建議?

張:首先你自己要培養一個知識上的累積與成長,你閱歷要廣,吸收不同型式的文化藝術,並關心時代與社會現象,有了這些基礎再去接觸各類型藝術作品,自然可以更加瞭解它想表達的意念與美學。

你不能只是一張白紙或缺乏準備。當然每個創作者的個性與風格都不同,我們要試著以寬視野、同理心去看,就會比較清楚進入裡面的那個感情連繫,有所感動。過於執著自己窄狹、獨斷的偏好去選擇,難免會錯失或犧牲掉許多美妙的觀賞經驗。

報:你可不可以跟我們談一下,你以一個編輯在編排攝影集的時候,你所考量的是那些面向?比如說921這種對台灣來說很大的事件,那你自己怎麼看?編輯《家園重見:走過921影像報告》(2000出版)這本影集時的想法是什麼?

張:這是(台灣媒體觀察教育)基金會的邀請,想做個年度回顧影集,劉振祥找我一起策畫。那時許多攝影家都在現場,拍的東西很雜,當時也出版不少相關影集。

我們不想重複舊踏,就慎選名單後找到幾位同儕好友,請他們以不同風格,如報導(梁正居、李文吉、黃子明、侯聰慧、金城財)、心象(顏新珠、劉振祥)、實驗(吳忠維)、檔案(沈昭良)、調查報告(張蒼松、許伯鑫)等不同方式與角度來表現921議題,並整理、設計一些「對照」的圖像 (林錫銘、杭大鵬)以凸顯災害現場的變遷差異,最後再依據主題、事件、攝影氛圍與風格等章節來編輯這本書。

我們還徵件、鼓勵當地居民拍照,請他們提供,同時將他們的照片放到書本結尾。我們試着從各角度、面向切入,除了展示攝影家的視角以外,也傳達受害災民如何觀看他們自己的家鄉。這本影集就像《看見淡水河》(1993)、《看見原鄉人》(1997)一樣,有較長時間參與事前規劃與設計,並不只是事後選輯照片而已,所以對主題可以多作彌補與綜觀。

報:這個是不同攝影家所集結成一本,有一些是只有一個人,比如說許村旭的《派對走掉》(2015)這本,同時這本有彩色、有黑白,面對這種組成的不同,你在編輯上是怎麼去成立最後的結果?

張:編個人專輯跟編合輯是很不一樣的,因為合輯有不同風格、調性的圖像,你必須要整個打散開來再整合。

編輯攝影集很像音樂家寫一首曲子,或是拍一部電影或紀錄片,它有起承轉合,一開始可能先醞釀,然後逐漸出現第一個主題,往前推展、變化,稍作休息後,再建立第二個主題,慢慢到高潮再安靜下來,如此反覆來回。基本上要有起承轉合的段落與韻律。

此外還得同時考慮很多因素,比如說色調,每個連接點與獨立章節要保持一個均衡的形式,這樣讀起來才不會跳tone。

當然,影像的調性更重要,調性包含情緒、狀態、速度、明暗、色系、風格等配置,你不宜把一幅很軟性氛圍的沒道理地硬接上一張張力十足的去比對;很沈重的,旁邊擺一張輕盈的,這都是不搭調的。事件進行時序也要有所追循,不宜過去與當下、時間與空間隨意穿插亂跳。

還有就是它的構圖、視角、方向、比例等,在銜接時都要考慮進去。所以當你手上掌握愈多照片的時候,你的選擇性就愈大,就像你拍片的時候拍了很多毛片,剪接的時候就可以有很多可能,有許多可變性,材料不夠多,就會受限,影響整個編輯結果。

編書時我們常常就是把照片舖滿整個地上,然後一個人就在那邊撿來撿去、排來排去,處理個好幾天,甚至有時候編輯完成隔天要印刷了,一覺醒來突然又覺得不對,趕緊調換。偶而也會在攝影集出版後,才覺得另一種編法會更有味道。

總之,編輯是充滿各種有機變化的。

報:如果像你編過這麼多書,要是有一個攝影家你並非熟識,在這樣的情況下,是要先暸解他還是⋯⋯

張:我不認識?那我可能不會幫他編吧。(笑)

要找我編書,大概都會有些熟悉的,如果不認識,我大概會說:「對不起!」除非他拍得特別有一套,令人驚豔的那一種,那我可能會動心。

編輯的前提是你要欣賞他的作品,即使是很熟悉的朋友,如果不喜歡或對他的作品無感,那就要請他另尋高就。培養編輯跟培養拍照一樣,隨着你的閱歷與經驗成長。你累積的知識與見識就會幫助你去選照片、做編輯。所以做為編輯的人,他的喜好與閱歷,不應只有攝影而已,應該包含其他東西,比如文學、美術、音樂、電影等等的接觸,因為這些都會影響到剪輯的概念。

報:你編過最難編的書是哪一本?

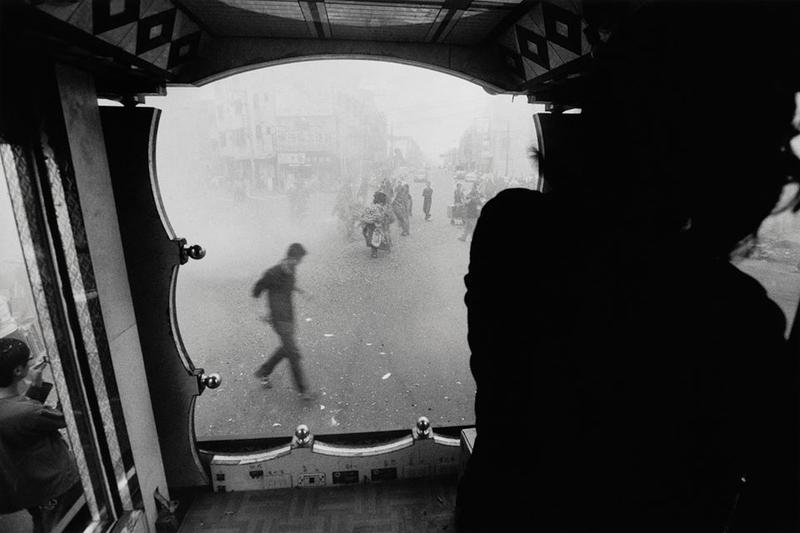

張:(笑)每一本都很難編,最近沈昭良要編一本他的新書《台灣綜藝團》,這本就很難編,他拍了一大堆照片,有各種不同的人物、事件與情境,我們好幾次鋪開這些照片,反覆編排,又不停加照片進來。他拍的東西很雜、又多,裡面的變化不少,不好理出一個頭緒,蠻頭痛的。

編輯一本紀實的攝影集,有時候素材雖夠,但缺少一些中間緩衝的、對比的,或是段落之間轉折的,貫穿上也會很麻。

要結構一本攝影集或一組系列專題,不一定要每張都要精彩、極致的,編輯起來,反而因張力緊繃、對峙,而互相抵銷力量。中間一定要有一些停頓、放空,讓人有想像的延伸空間。

好的拍攝家拍照時不只注意主場的焦點照片,週邊的配置與細節也會一併關心,要提高警覺注意瞬間發生的,也要同時靜下心來捕抓容易疏忽的微末角落。

因此,構圖、視角的變化、靜與動的營造、時空與氛圍的掌控,不要過於單一與侷限,要想辦法多層次、多方位探求。在這種專業態度下產生的照片,編起書來就會很精彩。

報:你還沒回答那一本書比較難編,除了《台灣綜藝團》之外,還有沒有?

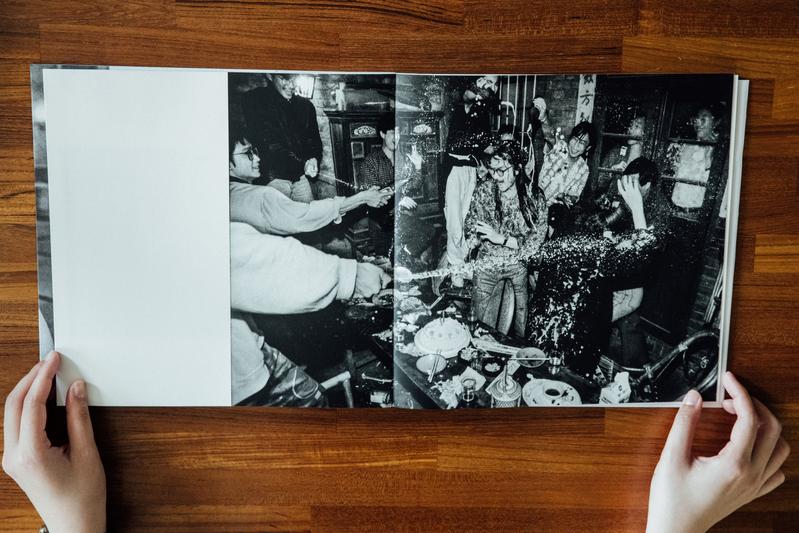

張:許村旭的《派對走掉》也不好編,因為東西也太複雜,他本來拿給我看的大都是一些解嚴前後的議場生態和街頭抗爭,多偏向新聞報導的社會紀實照片。

雖然他敏銳的嘲弄與批判角度高人一等,但我跟他說光是這樣不夠,會變成只是一本攝影記者的回顧影集。我認為如果要做一個優秀的攝影家不能只有新聞報導照片,應該還要有其他作品。

村旭請我幫忙編輯後,我就一直請他回去再挖照片,他也不斷找出一些我要的東西。我在編這本書的時候,前後章節擺的並不是政治嘴臉或街頭抗議的照片,而是一些屬於庶民的時代感或存在感的圖像,有天真無邪的,有百般無奈的,也有失魂落魄的⋯⋯這些更富普遍性、社會性與代表性,也更有攝影性。

專注在政治性上有點偏狹了,攝影應該更關心到廣大的人性上。

報:據知許村旭這本書有些作品是彩色正片,最後在印書時轉成黑白,關於這點好像是你的建議?但《家園重見:走過921影像報告》那本就彩色黑白交錯?

張:《派對走掉》當然不能放彩色的,因為這本書基調上是黑白的,較直接、強烈,他的彩色照片不多,也弱,不如整體用黑白表達。

《家園重見》那本不太一樣,這本影集有很多人參與噢,大都用彩色數位在拍,彩色照片在災變現場更有現實感的味道,它的真實性更傳神,也有說服力,因此彩色與黑白分章節交叉使用。

報:好像彩色跟黑白一起編對印刷來說似乎是一種考驗?

張:其實彩色好印,黑白較難印。彩色反正就是四色嘛,基本上不會差太多,黑白才難。

用四色印黑白,一不小心,版與版之間常發生色偏的誤差,很難整合。用套色印黑白,如果特別色沒調好,每個版印出來也不統一。一本攝影集如果夾雜彩色與黑白照片,分版時還要想好它的位置,以節省印刷費並兼顧它的品質。

報:你可以舉一個或幾個例子,你認為這幾本書或哪幾本書是編輯得比較好的?

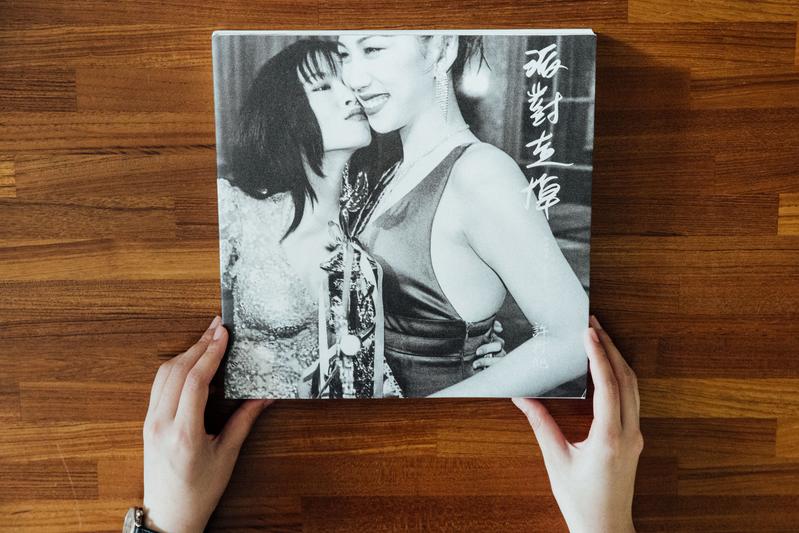

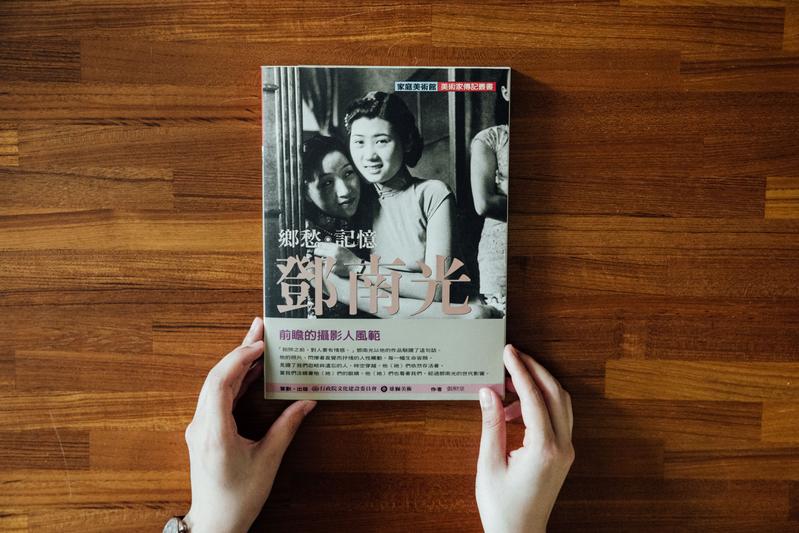

張:《鄉愁.記憶:鄧南光》(2002)我覺得是比較好的,這本我花了很多時間整理,因為書裡分成六個世代,包含童年記憶、東瀛寫真、時代紀事、社會風景、影會年代,生命容顏等,依據它的時間序、與空間變遷去發展,再以高質感的照片搭襯。

鄧南光的攝影集目前出版了不少,但是在這本書裡面,梳理分明、質量兼顧,照片與編排都很精彩、大方,並且有詳細相關資料考據,的確花了相當精力去編輯。

報:當初編這本書的機緣是如何開始的?

張:1992年文建會有一個「家庭美術館-美術家傳記叢書」的計畫,由《雄獅美術》負責執行,一開始都是介紹畫家,後來開始把攝影家帶進來,第一位入選的就是鄧南光,後來還有張才、李鳴鵰三劍客,當然還包括郎靜山。

當時李賢文找上我看能不能幫忙,其實我在這個之前,就已經幫鄧南光編過兩、三回照片了,1989年的《臺灣攝影家群象》叢書專輯(1),1993的《看見淡水河》、1997的《看見原鄉人》、1997的《女人‧臺北》,1998《老‧臺北‧人》等都整理過他的照片。加上後來紀錄片的訪問,包括他家人談了許多往事,提供一些器材、文物,書輯、底片、印樣等,一步一步再分階段撰稿謄寫、編輯照片,花了將近一年才完成。

報:「三劍客」是你發明的嗎?

張:當然不是!那是1948年新生報在淡水沙崙辦了一個攝影比賽,有很多攝影家參加,結果張才得了第一名,鄧南光跟李鳴鵰分得第二名,他們三個同時包辦前面三名,當時較年輕的攝影家黃則修事後回憶說,「三劍客」這個稱呼是他首先喊出來的。

後來他們三人都在台北市中心開起照相器材行,成立學會,提供獎金與材料資助鼓勵年輕人,熱心推展攝影活動,「三劍客」之名就一直流傳下來。

報:可是你編過這麼多書之後,你怎麼去思考?因為年紀會變、思考會變,不同的年齡會有不同的想法,你從年輕到現在,你怎麼看自己這個轉變的過程?

張:很難講得清楚啊,你總是跟著年紀與成長經驗去調整自己的思考與行為。

年輕的時候會比較生猛、蠻撞一點,年紀大了以後,難免會變得溫和,退卻一些。年長的優點是成熟與從容,缺點是猶疑與多慮,不像年輕那麼爽快、有勁。我們只有隨時警惕自己、告誡自己,要持續吸收、不斷更新,兼容並蓄,努力向前。

(Translated & Edited / Catherine Tan EK & Valence Sim)

Q: How do you look at a group of photography works? How do you understand different styles of reading?

A: In general, there are 3 ways to look at the works.

Firstly, there is viewing at an exhibition hall which you can study those pictures carefully. If the venue is quiet, you can even view each picture at your leisure, carefully studying every picture’s subtle layer, detail, texture/quality. Using music as an example, this would be akin to listening to a concert because there is direct impact and feelings (of being touched) from actually being there.

The second is to read photo books. This is different from exhibitions. In an exhibition hall, you are surrounded by that space, you are embraced by that atmosphere. When you are reading a book, you own the physical book. With it, you can read anytime; slowly, quickly, from front to back, over and over again and break down its editing style. You can have more time to mull over it and compare.

However, if one were to compare a printed product with actual photos, it is hard to feel the photographer’s air, feelings or aura. This is like buying a music record home. It is different from what you would experience at a live performance.

The other type is to view on the Internet. Due to the characteristics of the medium, it is fast, light and portable. Through the screen, images are luminated with light so images create a 3D illusion more easily and the colours are much stronger. But it is a phase. Images do not leave strong impressions easily after viewing. If one really wants to read and study photography work, I feel printed media is more convenient and suitable because you can read it anytime, concentrate on it, think over it, think over its background, setup, structure as well as the relationships between elements from start to twists to end, on how it impacts the narrative. Compared to other formats, reading photobooks is more beneficial.

Q: What suggestions do you have with regard to reading a photography work?

A: First, you have to accumulate and grow in knowledge. Read widely, absorb different types of artistic works and stay concerned with trends of current times and society. With this foundation, you’ll naturally have greater understanding of its message and beauty when you approach different types of artistic work. You cannot be just a piece of blank paper or lack preparation.

Of course, each creator’s personality and style is different. We need to try and view the work with broader horizons╱with open mind and empathy, which we will then be able to enter into a clearer emotional connection with the photographer, and be moved by the works. Being overly stubborn with one’s own narrow minded and myopic preferences will inevitably result in many missed opportunities for more wondrous viewing experiences.

Q: Can you tell us about what you consider as an editor when you are editing photography works? For example, 921 was a major incident to Taiwan. What do you think? What were your thoughts when you were editing 《Seeing Homeland Again: A Journey through 921 Photo Report╱家園重見:走過921影像報告》 (published in 2000)?

A: This was an invitation from Taiwan Media Watch to do a retrospective photography collection of the year. Liu Zheng Xiang╱Liu Chen Hsiang got me to plan this together. At that time, many photographers were also around, the works were very varied and there were quite a few photobooks published at that time too.

We didn’t want to do the same thing so we carefully selected a few close friends and invited them to show 921 through different approaches and angles such as reportage (Liang Zhen Ju, Li Wen Ji, Huang Zi Ming, Hou Cong Hui, Jin Cheng Cai), mental imagery (Yan Xin Zhu, Liu Zheng Xiang), experimental (Wu Cong Wei), archives (Shen Zhao Liang), investigative reports (Zhang Cang Song, Xu Bo Xing) as well as organizing and designing some contrasting images (Lin Xi Ming, Hang Da Peng) to bring out the changes and differences in a disaster area. Finally, the book was edited into chapters according to theme, incident, photographic atmosphere and styles.

We encouraged the locals to shoot and asked them to contribute their pictures to the ending of the book. We tried to approach the topic through different angles. Besides showing the perspective of a photographer, we also wanted to convey how disaster victims view their hometown. This photobook is similar to 《To Have Seen The River╱看見淡水河》(published in 1993)、《To Have Seen Natives╱看見原鄉人》(published in 1997). It was pre-planned and designed over a longer period of time, and not just a selection of pictures after an incident hence we can have an overview of the topic and make up for many areas.

Q: This was a book made up of works from different photographers. Some books consist only of works from one person. For example, Hsu Tsun Hsu’s 《The Party is Over╱派對走掉》 (published in 2015). The book has both colour as well as black and white images. How did you decide on the final work as an editor faced with such differences in the work?

A: Editing a solo work is not the same as collective work because collective work has many images of different styles and tones so you have to tear everything apart and put it together again.

Editing a photobook is like a musician writing a song or filming a movie╱documentary. It has rhythms – the ups and downs, climax and low point. It may be a slow build up initially, then the first theme may emerge followed by development, more changes and a short rest before the formation of the second theme, till it slowly builds up and reaches climax before quieting down again. We go back and forth like this repeatedly for many times. Basically, it has to have a structure and rhythm.

At the same time, one has to consider many elements such as colour tones. Every transition and individual chapter has to maintain a certain kind of balance so that the tones will not jump when the work is read.

Of course, the tone of the images is even more important. This may include different emotional states, conditions, speed, light and darkness, colour series, style etc. Thus it is not advisable to pit a picture with a soft atmosphere against a strong one. It will be too much. To put a frivolous one next to it is not compatible as well. The sequencing also has to abide by a certain order. It is not advisable to jumble present time, time and space sporadically.

There is also structure, angle, direction, proportions and so on to be considered in sequencing. The more images you have, the more choices you have. It is just like you have more to edit when you film more. There is more flexibility for change. Without sufficient material, there will be limits and it will affect the whole product.

In editing books, we frequently lay out the images all over the floor then one person may spend a few days picking and arranging them. There are even times when the edit is ready to go to print the next day but we suddenly feel something is amiss and need to change it quickly. There are also times when we feel another style of editing might produce more flavour after a book is published.

In conclusion, editing is full of different types of organic changes.

Q: You have edited many books. If there is a photographer that you are not familiar with, do you first understand the person or...?

A:If I don’t know (the person)? I probably would not help the person to edit. (laughs)

People who ask me to edit are likely people I am familiar with. If I do not know them well, I will probably say “Sorry!”, unless the person’s work is unique and astonishing, then I might be tempted.

The premise of editing is you admire a person’s work. If you do not like or have any feelings towards a person’s work, please ask him/her to go to someone else even if you know the person well.

Nurturing editing is similar to nurturing photography. As you grow and gain experience, your accumulated knowledge will help you in choosing pictures and making edits. An editor’s preferences and resume should not only be just in photography. It should encompass other things such as literature, art, music, movies and so on, because this will affect one’s concept of editing.

Q: What is the most difficult book you have ever edited?

A: (laughs)Every book is difficult to edit. Recently, Shen Zhao Liang wanted to edit his new book 《Taiwan Variety Circle╱台灣綜藝團》. This book was very hard to edit. He had taken a lot of shots with different subjects, incidents and situations. We had laid the images out so many times, arranged and rearranged repeatedly and added images. He had shot so many different things with quite a lot of changes within. It wasn’t easy to make sense of. It was quite a headache.

Sometimes making a smooth connection throughout a documentary work can be difficult even if you have sufficient material but lack elements to slow things down, contrast and create transitions.

Not every picture in a photobook or series needs to be exciting and captivating. In editing, this may cause images to fight and cancel out each other’s impact and strength because of excessive tension. There must be pauses, space and room for imagination in between.

Good photographers not only notice the main areas or key photos, but also pay attention to surrounding details and setups. One has to be alert to any instantaneous changes but also be able to quieten down to capture easily neglected corners.

Hence, don’t be too one sided with regard to structure, angle, movement and silence, control over space and atmosphere. Try to think of ways to explore from different levels. Be versatile. It is more exciting to edit photos taken with such professional attitude.

Q: You have not answered which book is difficult to edit. Are there others besides 《Taiwan Variety Circle╱台灣綜藝團》?

A:Xu Cun Xu╱Hsu Tsun Hsu’s 《派對走掉 The Party is Over》 was not easy to edit as well because it was too complex. Initially, most of the pictures he brought me were inclined towards news reportage pictures of scenes from street clashes after the curfew.

Even though he was sensitive and skilled in satire, I told him this was not enough. It will only become a photographer’s retrospective collection. I felt an excellent photographer can’t only do news reportage images and should have other works.

After he asked for my help to edit, I kept asking him to go back and dig for more images. He continued to find things I wanted. When I was editing this book, the chapters at the start and end did not focus on politics or street protests, but of ordinary people and their existence. There were the innocent ones, the helpless ones,the lost ones⋯That has a much greater reach and a greater representation of society as well as more photographic value.

To focus on politics is too narrow for a photographer. Photography should be more concerned about a wider spectrum of human nature.

Q: From my understanding, Hsu’s book had images that were taken in colour but the book was printed in black and white. This seems to be teacher’s suggestion? But 《Seeing Homeland Again: A Journey through 921 Photo Report╱家園重見:走過921影像報告》 had both colour and black and white?

A: “The Party is Over” can’t be in colour because the fundamental tone of the book is black and white. It is stronger and more direct. He did not have a lot of images in colour and they were weak so I might as well express the whole work in black and white.

《Seeing Homeland Again╱家園重見》 is a different book. That book involved the participation of many people. Most of them shot in colour, and color images have a greater sense of realism for disaster scenes. Its realism is more impactful and persuasive to the readers, so a mix between colour and black and white was used.

Q: Having both colour and black and white seems to be a challenge for publishers?

A: Actually colour is easy to print; black and white is harder. There will not be major differences if colors were used because it’s CYMK. However, black and white photos are harder for publishers.

Colour differences often occur when using CYMK to print black and white because of differences in the tonality of the colors, hence it’s harder to adjust. This goes the same if we were to do the same even for black and white, if we do not make accurate adjustments to the colors. If a photobook has both colour and monochrome images, the editor must really think through the layout carefully to reduce printing costs yet maintaining the quality of the body of work.

Q:Can you give one or several examples of books you felt was/were well edited?

A: I felt 《Homesickness. Memory: Deng Nan Guang╱鄉愁.記憶:鄧南光》(published in 2002) was one of the better ones. This book took me a long time to organise because the book spans 6 sections including childhood memories, japanese photography, current news, social landscape, movie era, images of daily life etc. It developed according to timeline, space changes and was accompanied by high quality images.

Deng Nan Guang had published quite a few photobooks but in this book, it was well organised, quality and quantity were well taken of and photos and editing were exciting - elegant coupled with detailed reference material. It did take quite a lot of energy to edit.

Q: How did the chance to edit this book come about?

A: In 1992, the Council for Cultural Affairs had a plan for 《Family Gallery – Artists’ Biography Series╱家庭美術館 – 美術家傳記叢書》 to be carried out by Lion Art. In the beginning, it introduced mainly painters but after a while, photographers were included. The first candidate was Deng Nan Guang. After that, there was Zhang Cai and Li Ming Diao of The Three Musketers and of course, Lang Jing Shan was included as well.

At that time, Li Xian Wen asked if I could help but actually, I had already helped Deng Nan Guang edit photos several times before in works such as 《Aspects and Visions╱臺灣攝影家群象》 Series 1 in 1989,,《 To Have Seen The River╱看見淡水河》in 1993,《To Have Seen Natives╱看見原鄉人》in 1997、《Woman. Taipei╱女人‧臺北》in 1997,《Old. Taipei. Person╱老‧臺北‧人》in 1998 and so on. On top of that, there were also documentary interviews that included many past stories from his family. We were provided equipment, artifacts, books, negatives, contact sheets etc. These were turned into essays step by step along with editing of photos. It took one year to complete it.

Q: Was “The Three Musketeers” your idea?

A: Of course not! In 1948, Shin Sheng Daily News organized a photography competition in Tamsui Shalun. Many photographers participated. In the end, Zhang Cai won first prize, Deng Nan Guang and Li Ming Diao shared the second prize. The three of them won the top three prizes. A younger photographer Huang Ze Xiu╱Huang Tse-Hsiu coined the term “The Three Musketers” after that.

Eventually, the three of them opened photography equipment stores in Taipei Central and provided scholarships as well as research support to young people through the setting up of institutes. They promoted photography passionately. “The Three Musketeers” continued to be passed down after that.

Q: How do you think after you have edited so many books? As one ages, one’s thinking will change and have different thinking at different age. How do you see your process of change from young till now?

A: This is hard to say clearly. You always adjust your thinking and ways according to your age and growth experiences.

When one is younger, one tends to be more aggressive and reckless. As one grows older, one can’t help but mellow a little and become gentler. The advantage of age is maturity and calmness. The downside is indecisiveness and excessive worry. One is no longer as straightforward and energetic. We can only constantly remain alert and warn ourselves to continue to absorb (new things), renew ourselves, learn different things and continue to hard work to push forward.

深度求真 眾聲同行

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

今年是《報導者》成立十週年,請支持我們持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,度過下一個十年的挑戰。