Prabowo Subianto, who rose to fame among young voters through unskillful dances and videos of him playing with cats on social media platforms like TikTok—and even successfully won the Indonesian presidency with this approach—quietly began deleting these humorous videos after his victory. Andreas Harsono, who has personally witnessed the military's involvement in politics and its alleged role in historical acts of ethnic violence, told me that the key factor in the 73-year-old Prabowo's electoral win was the strong support from young voters.

“Many Indonesians under 30 are unaware of his actions during his time as a military general,” Harsono said. “They only know him as a tough, wealthy, and influential politician from a prominent family.” During the election campaign, the focus shifted dramatically to his “beyond-politics” personal image, making politics itself no longer the core focus of any campaign activities.

Indonesia was spiraling ever-deeper into chaos in the last days of the 32-year Suharto regime. Inflation was around 50 percent and rising. There was looting and rioting. Numerous pro-democracy activists disappeared without a trace. Mass protests demanded the resignation of Suharto, as did even his own party caucus in the rubber-stamp parliament.

The 76-year-old dictator, however, did not flinch, as he believed he had the backing of the military. The generals had always been quick to send their troops to all corners of the country to suppress dissent, and—for now—the strategy still seemed to work.

Amien Rais, a Muslim leader and fierce Suharto critic, called off one of the planned demonstrations, which he had promised would bring 1 million Indonesians to the streets of Jakarta, saying: “Somebody told me, who happens to be an army general, that he doesn't care at all if ... an accident like Tiananmen will take place today.”

That was on May 20, 1998. As it turned out, Suharto would resign the very next day.

Rais never revealed the identity of the general who had threatened to crack down on the protest as violently as the Chinese government did when students demanded reforms in 1989.

One of the likeliest culprits, however, is Prabowo Subianto. At the time, he headed Indonesia's 27,000-strong Army Strategic Reserve Command.

Prabowo “did not hesitate to mobilise tanks, barbed wire and soldiers with automatic rifles to set up blockades on Jakarta's major roads,” wrote Andreas Harsono, then the Jakarta correspondent at The Nation, an English-language newspaper based in Bangkok.

As the son-in-law of Suharto, Prabowo had the ambition to succeed him one day. This opportunity, however, came too early for the young military commander, as he lacked support among the elites. He instead backed the imploding dictatorship until the very end, as other political and military heavyweights appeared to be ahead of him in the race to take over at the helm.

In contrast to many other elite figures, Prabowo was also not in the room when Suharto eventually stepped in front of the cameras to announce his resignation and tap his vice president, B.J. Habibie, as his successor.

After a failed last-ditch attempt by Prabowo to take control of the combined armed forces, Habibie removed him from his post on the first day of his presidency. His administration then established a military ethics council, whose months-long investigation found Prabowo guilty of ordering the kidnapping and torturing of 23 democracy activists. Prabowo admitted to it, but never acknowledged his responsibility, maintaining that “it was my superiors who told me what to do.”

The council didn't have the authority to press criminal charges, but Prabowo was dismissed from the military and went into exile in the Middle East.

For the next couple of years, there was no indication that Prabowo could ever stage a comeback. Instead, Indonesia embarked on a journey toward democracy. Reformasi, as it is called in the country, took hold and bore fruit, and Prabowo faded from people's memory.

Prabowo's path to resurrection was long, but in the end it seemed inevitable.

On Oct. 20, he was inaugurated as Indonesia's new president. He had won a remarkable 58.59 percent of the vote in the election on Feb. 14.

When asked, during the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival in Bali in late October, whether reformasi was over, Harsono, now a senior Indonesia researcher at Human Rights Watch, answered with an emphatic “yes.”

Prabowo won the election on the back of broad support from young voters, a development that Harsono, when I talked to him this month, said was only possible “because many Indonesians under 30 don't know what he did as an army general.”

“There's a gap between the younger and the older generation regarding Prabowo,” Harsono said. “Many younger people only know he's a strong politician who comes from a prominent family and has money.”

Prabowo is from one of Indonesia's most illustrious political dynasties. Prabowo's father, Sumitro Djojohadikusumo, held several ministerial roles, including in the early Suharto years. Prabowo's grandfather, Margono Djojohadikusumo, was the country's first central bank president.

Prabowo grew up in Jakarta and abroad, where he received an elite education in Switzerland, Singapore, Thailand, Malaysia and the UK.

Both his father and grandfather were economists, and the family had no obvious connection to the military. During Indonesia's struggle for independence from the Netherlands in the late 1940s, however, Sumitro understood that the armed forces would always play a decisive role in the country. He encouraged his son to pursue a military career.

Prabowo rose in the ranks quickly, in part because he showed that he could be ruthless. His alleged involvement in a 1983 massacre in East Timor, in which about 200 civilians were killed, is well documented, but the military never conducted an investigation.

After the kidnappings during the downfall of Suharto and the subsequent ethics council investigation, however, Prabowo was a disgraced figure in Indonesia and abroad. The US banned him from entering the country under a law targeting human rights offenders.

His political ambitions were undiminished though. After returning to Indonesia in 2004, Prabowo ran for vice president in 2009, and for president in 2014 and 2019, but his notorious human rights record and inconsistent politics—he evoked strongman nationalism in 2014, and Islamism five years later—mobilized too many voters against him.

Ahead of this year's election, he embraced a whole new persona again: That of the “dancing grandpa,” whose videos would reach more voters on social media than any other candidate, helping him over the line in his third attempt.

In the months ahead of the election, almost every public appearance of Prabowo produced videos, immediately shared and reposted by his followers, that showed him dancing—not particularly skillfully, but always in a way that made 73-year-old Prabowo look affable.

Official campaign videos featured a digital avatar of him dancing with Indonesians from all walks of life, from corporate employees to rice farmers and worshipers in front of a mosque. With the stubby avatar being smaller than all the real-life actors in the videos, the new Prabowo no longer looked like a ruthless military commander. Videos of him playing with cats were also among the popular favorites.

“The rebranding of Prabowo, particularly on TikTok, didn't emerge organically. It was obviously the result of a cunning marketing strategy that was designed to target the Gen Z [people born from 1997 to 2012], who made up about 20 percent of the electorate in the last election,” said Ary Hermawan, a digital populism researcher at the University of Melbourne.

“This campaign worked well because TikTok bans overtly political content, but this doesn't mean the platform cannot be used for political campaigning.”

Hermawan, who previously worked as an editor at the Jakarta Post, attributes Prabowo's success to an “artificial grassroots” campaign in which a large number of social media users, called “buzzers” in Indonesia, were paid by Prabowo's elite backers to share pro-Prabowo content.

“Political buzzers become a force when they work in coordination with other buzzers to create the impression of a popular consensus,” he said.

The intended “consensus” about Prabowo was that he was no longer a threat.

“The buzzer campaign tried to whitewash Prabowo, to distract, to obfuscate” whenever his human rights record came up, Hermawan said.

Several factors made Prabowo, as Hermawan called him, “the man to beat in this election”: The young electorate, the widespread use of social media and its algorithms boosting light-hearted content, but also the general sentiment among Indonesians.

“This was not the case in the last election, which was much more personality focused,” he added.

The two other presidential candidates, Anies Baswedan and Ganjar Pranowo, initially ran negative campaigns attacking Prabowo, while the latter presented himself as a unifying figure above the political fray. Strongman nationalism or Islamism were no longer part of his message.

When Anies and Ganjar fell behind in the polls, they, too, focused increasingly on social media content seeking to go viral. Politics no longer took center stage in any of the campaigns.

Prabowo was first appointed to a government position in 2019, when he joined the Cabinet of then-president Joko Widodo, who is widely known as Jokowi.

Prabowo had just run an unsuccessful presidential campaign against the incumbent, relying on angry, Islamist messaging. When he was defeated, by over 10 percentage points, he accused Jokowi of stealing the election from him. Riots ensued in Jakarta, killing at least eight people. To ease tensions with the Islamist right, Jokowi offered Prabowo the position of defense minister.

The move was initially seen as a mere marriage of convenience. Prabowo and Jokowi, who was in his last term due to a constitutional term limit, positioned themselves as figures of different political camps: Jokowi as the liberal reformer, Prabowo as the pious military man.

Nearly five years later, in the fall of 2023, Prabowo was leading in the polls by about 5 percentage points, on the back of high approval ratings for the administration of Jokowi, who had made a significant move to the right, and was now seeking to establish himself as the progenitor of a political dynasty, too.

Prabowo, who had not tapped a vice presidential candidate yet, was the unexpected yet logical choice for Jokowi to throw his weight behind. Jokowi backed Prabowo's candidacy in an astonishing volte face, and his eldest son, Gibran Rakabuming Raka, became Prabowo's running mate.

Prabowo's lead in the polls doubled within a few weeks. He was now the continuity candidate, and more importantly perhaps, he “inherited” the support of business and media elites firmly aligned with Jokowi, as well as his team of buzzers. With a united force of content creators on social media and ample funding for their work, his popularity kept surging.

However, in contrast to other politicians from around the world who are associated with a strong social media persona—from US president-elect Donald Trump to Ko Wen-je (柯文哲) in Taiwan, who ran his unsuccessful presidential campaign largely on TikTok—Prabowo did not portray himself as an “anti-establishment” candidate. As someone who “was groomed to become president from a young age,” as Harsono described him, Prabowo instead adopted a multi-pronged strategy that included elements of traditional campaigning, including founding a newspaper to promote his agenda, while bypassing the established channels whenever he saw fit. Disinformation about his past was being promoted and deepfake videos of his opponents made the rounds online, but the image his campaign sought to create was markedly not polarizing or hateful.

During the long eight months between Prabowo's election victory and inauguration, the videos of him dancing or playing with cats disappeared from his social media accounts.

“At this point, Prabowo really wants to be taken seriously,” Hermawan said.

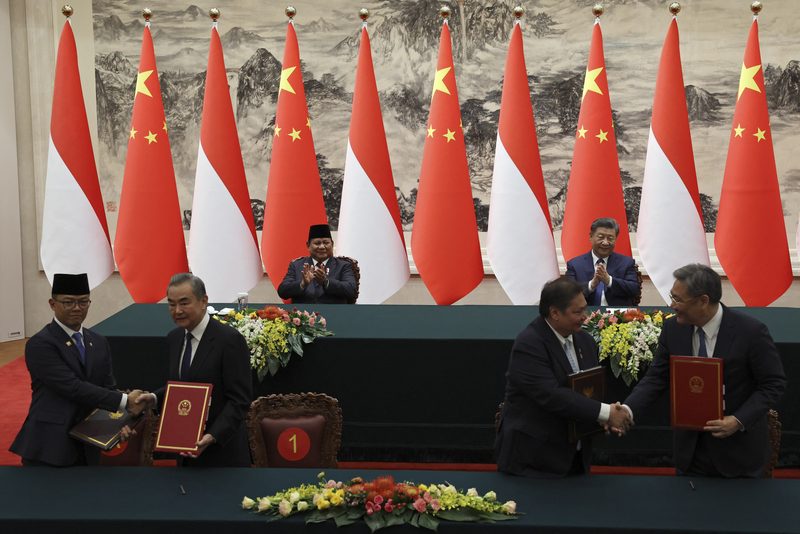

His accounts now show him shaking hands with other world leaders, for example during back-to-back meetings with Chinese President Xi Jinping (習近平) and US President Joe Biden shortly after taking office.

To those who looked beyond TikTok during his campaign, Prabowo had promised to continue Jokowi's pragmatism in foreign policy and strike a balance between trade with Beijing and cooperation with Washington—a quest that is central in times of heightened US-China tensions.

China is Indonesia's largest trading partner, and Beijing has invested heavily in the country's infrastructure. During Jokowi's second term, Indonesia and China have also deepened their cooperation in the mining sector, specifically nickel, which is a main ingredient of batteries used in electric vehicles.

Indonesia is the world's largest producer of the metal, but it had—until China stepped in and set up processing facilities in the country—relied solely on exporting the raw material.

Jokowi had hoped China would help Indonesia climb up in the value chain in the nickel sector, but as it turned out, reliance on China increasingly limits Indonesia's access to other markets, specifically the US and its allies, as Washington has imposed restrictions on “Chinese” nickel in Western products.

How Prabowo will manage such issues in the long run, as a political heavyweight with little foreign policy experience, remains to be seen.

Last month, a joint statement released after his meeting with Xi in Beijing offered a glimpse at challenges to come.

In the statement, Indonesia and China said they had “reached important common understanding on joint development in areas of overlapping claims” in the South China Sea.

The problem is that “overlapping claims” only exist if Indonesia accepts that most of the sea belongs to China, as Beijing claims on the basis of its “nine-dash line” map from the 1940s, which it has increasingly relied on in recent years as it seeks to enforce regional supremacy. Until the statement, Indonesia, alongside all other ASEAN members, had rejected China's claim, citing a Permanent Court of Arbitration ruling from 2016.

Indonesian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sugiono, who had been involved in the talks in Beijing, spent the next couple of days trying to convince Indonesia's regional allies, as well as lawmakers in Jakarta, that Prabowo had agreed to the statement “in a bid to reduce tension,” but that it did not mark a change to the government's stance.

It seems neither Prabowo nor his top diplomat and confidant were fully up to the task during their first foray into the international arena.

“Prabowo appointed an inexperienced foreign minister,” Harsono said. “Sugiono is Prabowo's former personal secretary. Prabowo offered him the job just because he [Sugiono] is loyal to him.”

“Sugiono does not understand that the agreement [with China] is problematic,” Harsono added.

Bolstering food security was another campaign promise of Prabowo, and his messaging since his inauguration shows that he is serious about it.

UN World Food Programme figures show that 8.5 percent of Indonesian children are undernourished, and the idea to improve the situation is not controversial. The way in which Prabowo is expected to approach the issue is problematic though.

One of his first acts in office was to restart a Suharto-era “remigration” program to the Indonesian part of Papua, a vast region in the far east of the country that has seen decades of violence involving the military and local armed groups. The central government has long been accused of well-documented human rights abuses against the Indigenous population in the resource-rich region.

Under Prabowo, large swaths of forest in southern Papua are expected to be developed into farms, likely to be owned and run by Indonesians resettled there from other parts of the country.

“This is dramatic, this is dangerous, this is going to prolong discrimination against Indigenous Papuans,” Harsono said.

“It remains to be seen what the program will look like, and in what ways it will be different from the Suharto-era policy,” he added.

The main problem, however, is that Indonesia has already seen significant democratic backsliding during the second Jokowi term, and under Prabowo this is expected to continue, Harsono said, citing a new criminal code that pushes secularism to the side, as well as weakened environmental and labor regulations.

“The middle class is bearing the burden of those policies,” he said. “Not so much the poor, who receive government handouts, or the rich, who are benefitting from new forest concessions and mining permits.”

The second Jokowi term has also seen increasing tensions between local communities and foreign employers, specifically Chinese firms.

“I'm nervous about Prabowo's presidency,” Harsono added, especially as Indonesia has often seen violence against minorities—most often Indonesians of Chinese heritage, but also other groups, including Muslims in non-Muslim-majority regions—and Prabowo has played a well-documented role in that.

The violent episodes usually started when there was an international crisis, Harsono said, adding that it might happen again.

“If, for example, there's a crisis over Taiwan—if, for example, Beijing decides to attack, it would be a very dangerous situation in Indonesia as well,” he said. “Many minorities in Indonesia are at risk.”

※This report was produced by The Reporter and the Chinese branch of Radio Free Asia (RFA).

(To read Chinese version of this article, please click: 從侵犯人權者到抖音總統:印尼普拉伯沃的漫長道路)

深度求真 眾聲同行

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

今年是《報導者》成立十週年,請支持我們持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,度過下一個十年的挑戰。