Growing up, my primary school teacher would regularly come by the family hardware store to tutor me. With aluminum kettles hanging over his head, porcelain bowls and plates by his waist, and loops of wire and stacks of oil cans by his feet, he helped me prepare for the high school entrance examinations.

He was from a village in Penghu, and came to Kaohsiung to pursue a better education. He was enthusiastic about my education, and because of his own experience, he urged my father to let me try for a better school in the capital, Taipei. It's as if, with this one sentence, he moved the rudder of the dinghy carrying me by just five degrees, forever changing my life's trajectory.

In September of 1979, I tested into Taipei First Girls' (北一女高中), the best girls' high school in the country, and waved goodbye to Kaohsiung. In the beginning I felt defeated by homesickness. I couldn't get used to Taipei, and I would visit home every weekend.

Back then, there was no high speed rail. The trains were rarely on time, and a trip from Taipei to Kaohsiung could easily drag on for nine or ten hours. On Saturday at noon I would rush to the train station as soon as my classes finished. I remember I would look out to see the sun set over the sea as the train pulled into Chunan Station on the way south. After spending only a night in Kaohsiung, it would already be time for me to return to Taipei. My brother took me to the train station on his Vespa scooter, and as soon as I sat down on the train and felt the engine's rumble, tears would flow down my face. I didn't dare to turn around and say goodbye to my mother one last time. At the peak of my homesickness I would write letters to her, asking her to look into transferring me to Kaohsiung Girls' Senior High School (高雄女中), telling her, "I want to come back to Kaohsiung!"

In those days, I wasn't the only student who moved to the capital by way of entrance examinations. About ten percent of the students at my school were from outside the Greater Taipei area, living away from home at age 16 or 17. We were referred to as "students from outside the region" (外地生). Some of us rented in the diplomatic dormitories behind the school, and I even heard there were students living in shacks run by nuns. Others like me lived with relatives, stir-frying the bitterness of living under the charity of others, and stewing the depression of living away from home.

In the first semester of my freshman year, in a practice essay for language class, the teacher gave us the prompt "the moral of a sentence." My classmates had just been passing along a school magazine from Jianguo High School (建國中學), the best boys school in the country, and I borrowed a passage:

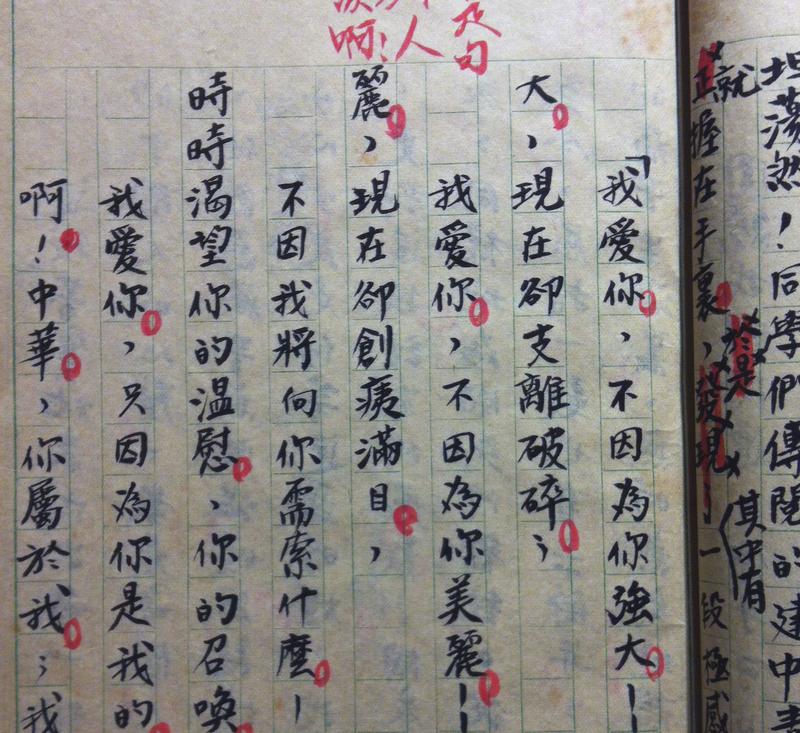

I love you, not because you are strong — you are indeed strong, but right now you are scattered and smashed. I love you, not because you are beautiful — you are indeed beautiful, but right now you are bruised and broken. It is not because I need something from you, but right now I thirst for your comfort, your beckoning! I love you because you are mine! Ah! China, you belong to me, and I belong to you!

On the page that this passage took up, the teacher had written in red pen, "each sentence truly brings passionate tears!" Continued on the next page were the thoughts of a homesick 16 year-old. I wrote that my feelings reflected "the feelings of all Chinese people who left their hometowns" who have spent every moment of the last 30 years thinking of home, and that as a student from outside the region, I was especially touched.

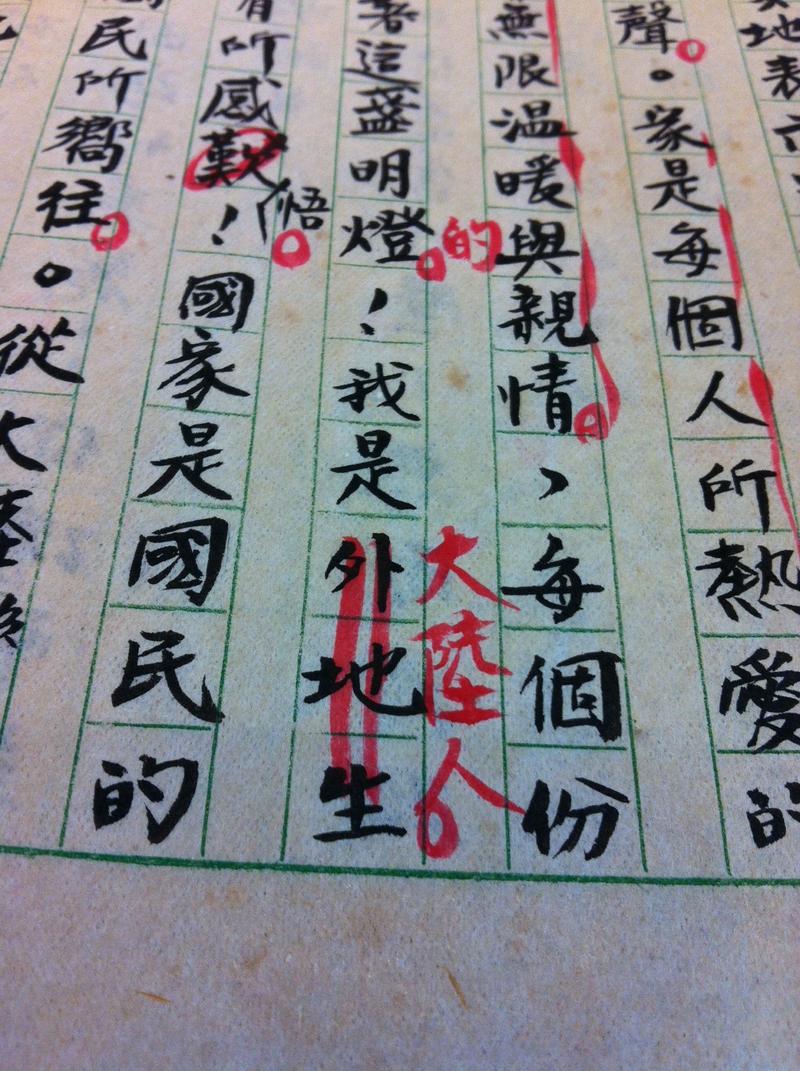

On this page, the teacher's comments were no longer passionate exclamations, and she drew two lines through the words "outside the region", as if putting them behind prison bars. And in an act of grand larceny, she substituted for me a new identity, writing in red ink the word "mainland Chinese".

Reading through my composition notebook 37 years later, my heart cries like a hostage in a world without justice. I wasn't from China, I was just a little girl from Kaohsiung who came to study in Taipei. But I wasn't conscious of this at the time.

I can't help but wonder if I my 16-year old self wasn't treated for psychosis. One injection after another made me forget all about the words "martial law" and "dictatorship." I heard about the Kaohsiung Incident during my first semester, and at the time, the only thing I wrote in my journal was that a military policeman was injured, and that the chief of the National Police Agency sent him 30,000 NTD in compensation. Upon receiving the funds, the policeman replied "what good is money, I want my country back." I wrote that this kind of "sentiment and obedience for one's country and countrymen" and "persevering spirit" were qualities that should be nurtured in all young students. I also naively believed the reason our school principal gave us for cancelling a school festival that was supposed to take place that December. Not only would there be "busloads" of eager boys trying to attend, but these were also "troubling times, and war could break war could break out at any moment." Not to mention that "Communist bandit spies were everywhere looking to incite students, just like they did in Beijing 30 years ago, precipitating the fall of the nation in such a short period of time!"

I experienced far too many bouts of hallucinations that year, swaying and stumbling but believing my footsteps were steady, looking through a dense fog but believing that my eyes saw light. I didn't know whether I could proclaim loudly to my teacher "I'm not Chinese."

(To read the Chinese version of this article, please click: 【戒嚴生活記憶】陳柔縉/老師,我不是大陸人 )

用行動支持報導者

獨立的精神,是自由思想的條件。獨立的媒體,才能守護公共領域,讓自由的討論和真相浮現。

在艱困的媒體環境,《報導者》堅持以非營利組織的模式投入公共領域的調查與深度報導。我們透過讀者的贊助支持來營運,不仰賴商業廣告置入,在獨立自主的前提下,穿梭在各項重要公共議題中。

你的支持能幫助《報導者》持續追蹤國內外新聞事件的真相,邀請你加入 3 種支持方案,和我們一起推動這場媒體小革命。